Excerpt from my current research on #PD #mobile #youth #justice

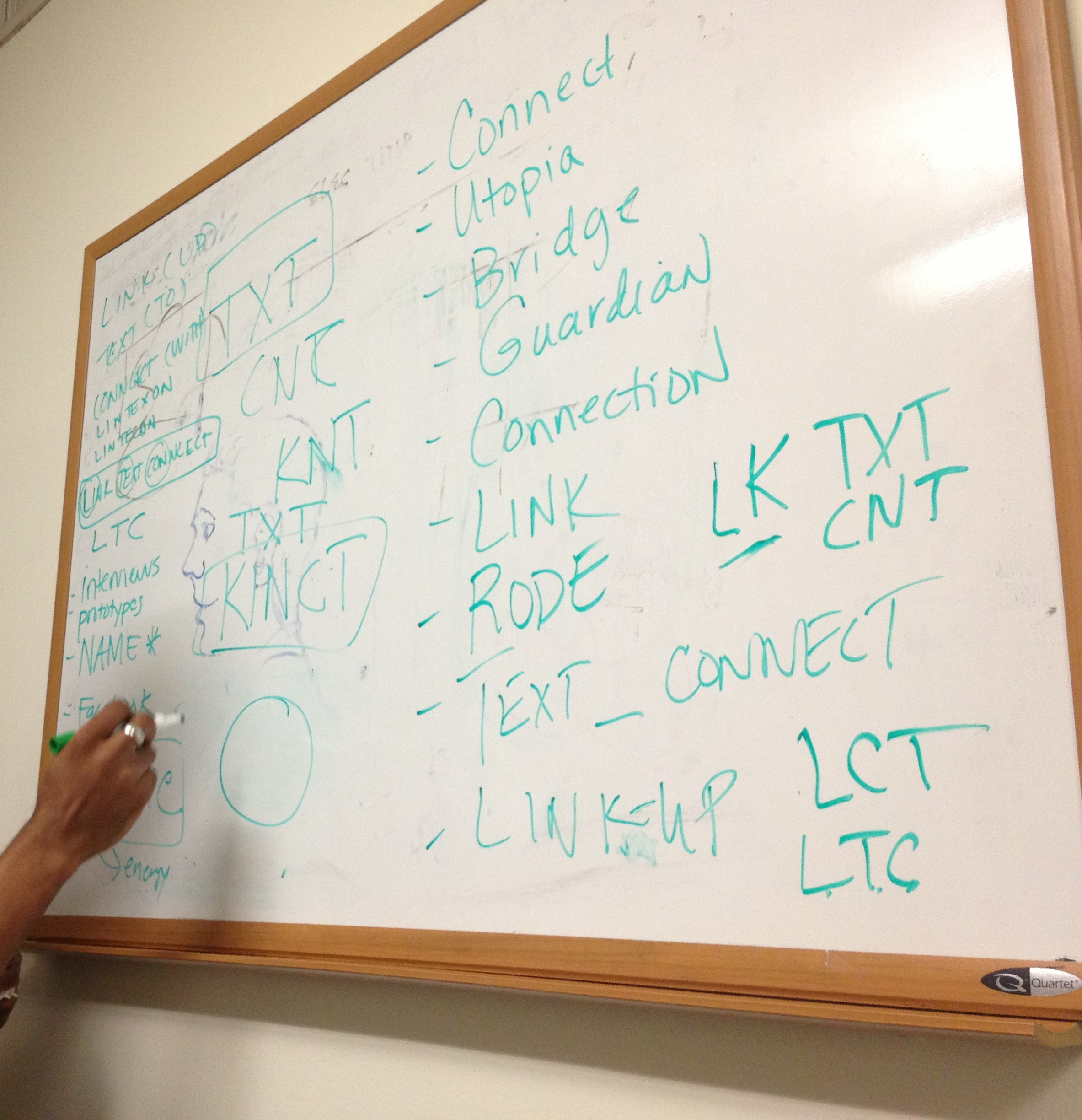

(Photo by Tara L. Conley)

The following is an excerpt from an article draft I'm currently working on about participatory design, mobile text messaging service, and court-involved youth:

During the summer of 2013 amid a controversial mayoral race in New York City[1], mayor Michael Bloomberg vetoed legislation that, in part, would create an independent inspector general to oversee the New York City Police Department (Goodman; 2013) and would allow for an expansive definition of individual identity categories under the current law. The four bills, together named the Community Safety Act (Communities United for Policing Reform; 2012), were brought forth by City Council as a result of a legal policing practice called Stop-and-Frisk. This policing practice allows New York City police officers to stop, question, and frisk citizens under reasonable suspicion of criminal activity.

While New York City residents were at odds over mayoral candidates and policing practices, young people involved in both foster care and juvenile justice systems were developing and designing a free text messaging service that would support court-involved youth in New York City to access resources and services using their cell phones. Three months before Bloomberg vetoed the Community Safety Act in New York City and while the city’s political sexting [2] scandal garnered national attention, several young people and I were discussing ways mobile technology could be used to help court-involved youth stay connected to their communities. Unaware about the extent to which Stop-and-Frisk and other safety concerns affected young people, I brought forth the idea of a text messaging platform that would primarily function as means of connecting court-involved youth to educational resources such as tutoring services and neighborhood jobs. At the time, the purpose of the platform was to create an intimate and anonymous means for young people involved in both foster care and juvenile justice systems to seek out resources beyond the institutions to which they were bound. Cell phones, I thought, would be the easiest and most comfortable way to facilitate a connection between young people and their communities.

However, the more I talked with young people, the more I understood that connecting to their communities not only meant accessing educational resources, job listings, and intervention services like hotlines, it also meant seeing the mobile device itself as a documentation tool and mobile companion for young people as they navigate the terrain of constant surveillance (Ruderman; 2013) and unstable home lives, all while trying to grasp for themselves a sense of belonging amid a psychological battlefield of metropolis dwelling [3].

Notes

[1] While running for mayor of New York City, former US congressman Anthony Weiner was involved in a national sex scandal, of which he admitted to sending sexually explicit text messages to several young women. Weiner’s indiscretions was the focal point of the NYC mayoral race and national news.

[2] Sexting is a term that describes the act of sending and receiving sexually explicit messages usually over a mobile device. The terms “sex” and “texting” began to appear in survey literature as early as 2008. Shortly thereafter the term “sexting” (a word formed by combining “sex” and “texting”) began to appear widely in academic studies and mainstream media and news (see The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy; 2008; Lounsbury, et. al.; 2011, and Ringrose, et. al., 2012).

[3] Simmel (1903) writes about the ancient polis, or city-state, as it relates to the small town. Both the city and town share an anxiety of “incessant threat” by outsiders, or enemies seen as outsiders. Simmel argues that because of this collective anxiety the environment becomes “an atmosphere of tension in which the weaker were held down and the stronger were impelled to the most passionate type of self-protection” (pg. 16). One might argue that the conditions young people experience in the city, particularly in New York City is symptomatic of an anxiety-ridden atmosphere.

References

Communities United for Policing Reform. (2012). About the Community Safety Act. Accessed on Aug. 5, 2013. Retrieved from http://changethenypd.org/about-community-safety-act

Goodman, D.J. (2013). Bloomberg vetoes measures for police monitor and lawsuits. The New York Times. Accessed on Aug. 4, 2013. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/24/nyregion/bloomberg-vetoes-measures-for-police-monitor-and-lawsuits.html?_r=0

Lounsbury, K., Mitchell, K.J., and Finkelhor, D. (2011). The true prevalence of “sexting”. Crimes Against Children Research Center. https://www.unh.edu/ccrc/pdf/Sexting%20Fact%20Sheet%204_29_11.pdf

Ringrose, J., Gill, R., Livingstone, S., Harvey, L. (2012). A qualitative study on children, young people, and ‘sexting’. NSPCC. http://www.nspcc.org.uk/Inform/resourcesforprofessionals/sexualabuse/sexting-research-report_wdf89269.pdf

Ruderman, W. (2013). To stem juvenile robberies, police trail youths before the crime. The New York Times. Accessed on Aug. 4, 2013. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/04/nyregion/to-stem-juvenile-robberies-police-trail-youths-before-the-crime.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

Simmel, G. (1903). “The Metropolis and Mental Life” translated and published in The Sociology of Georg Simmel, ed. Kurt Wolff (Glencoe, IL: Free Press, 1950), 409-424.

The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. (2008). http://www.thenationalcampaign.org/sextech/pdf/sextech_summary.pdf

Court-involved youth and social meanings of mobile phones

photo by Tara L. Conley

“The mobile is the glue that holds together various nodes in these social networks: it serves as the predominant personal tool for the coordination of everyday life, for updating oneself on social relations, and for the collective sharing of experiences. It is therefore the mediator of meanings and emotions that may be extremely important in the ongoing formation of young people’s identities” (Stald; 2008, pg. 161).

"Dependency Court involved youth rarely have access to a computer or cell phone, and even when they do, it is often only for a short period of time" (Peterson; 2010, pg. 7).

The following is a conversation about cell phones between me and young people involved in foster care and juvenile justice systems. This excerpt is part of ongoing research. Please do not republish.

Tara: I have a question. You all have cell phones, right? And they’re reliable? Do young people [who are court-involved] have cell phones? Do they have data plans? Do they have Smartphones? Do they have flip phones?

Male 1: Some of them have flip phones. Some of them have Smartphones. There are some of them who are scared to pull out their flip phones because...

Female 1: They may get picked on.

Male 1: Exactly!

Tara: They might what?

Female 1: Picked on.

Tara: Picked on? Really?

Male 1: Yes!

Tara: Because they have a flip phone and not a Smartphone?

Male 1: Yes!

Tara: That’s horrible.

Male 1: Kids are vindictive.

Male 2: If you still got a Blackberry you might get picked on.

Female 1: I have a Blackberry. How does that make me less of a person? Because I don’t have an upgraded phone like you?

Male 1: I like it! My Blackberry. I like it more because it’s more of a useful phone than the iPhone and the Galaxy.

Female 1: But you know what? I also think it’s the media that portrays it that way. Like we need it.

Male 1: Of course.

Female 1: It’s like water. Our tap water gets checked everyday to make sure it’s safe for our bodies, but [bottled water] might not get checked as much, but they make it seem like we need it more.

Male 1: But see, if you want to talk about that, that’s on a whole other level. That’s propaganda!

Female 1: But they make it seem like we need this special water.

Male 1: Yeah! They do that with everything! It’s how the government makes money off of the foolish.

Male 2: But then there’s a lot of girls who be like, ‘Oh, if you don’t have an iPhone 5, you’re not popular.’

[Laughing]

Male 1: Yup.

Male 2: The kids get into stuff like that you know. So, I mean there are some kids who don’t have a phone...

Tara: You have an iPhone?

Male 1: Yeah, the 5.

Tara: You have an iPhone?

Female 2: No, the Galaxy Exhibit.

Tara: But they’re all Smartphones?

Male 1, Male 2, Female 1: Yeah.

Male 1: Most of the time, look, it’s hard as hell right now to find a flip phone.

[Laughing]

Male 1: I’m not even going to lie, if you got a flip phone, I’m probably gonna laugh.

[Laughing]

References

Peterson, S. B. (2010). Dependency court and mentoring: The referral stage. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Stald, G. (2008). Mobile identity: Youth, identity, and mobile communication media. Youth, Identity, and Digital Media. Edited by David Buckingham. The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Media and Learning. pp. 143–164. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Transcribing data on a Sunday afternoon

Excerpt of transcribed audio from the first TXT CONNECT youth advisory board meeting on March 12, 2013:

What we’re doing is building a communication platform for these young people. It’s not just mobile text messaging. It’s Facebook--and another thing I was thinking with the Facebook page is to do exactly what you guys are saying and suggesting, which is to build this community online where young people can feel like ‘Okay, I know exactly where I need to go to get information.’ The platform that we’re trying to build--the purpose of it is to connect all of these resources together for young people. It’s like a one-stop shop for [court-involved youth] who want to get information about A, B, or C. They know they can go to whatever it is that we’re calling it.

The First Family and Their Cell Phones

On January 21, 2013, I sat glued to my television and computer screens while watching the pomp and ceremony of Barack Obama's 2nd inauguration. Of all the events, I was most drawn to the inaugural parade. For about an hour, I had the pleasure of catching a unique glimpse of the family's down-to-earthiness. I also got a chance to completely geek out while watching Sasha, Malia, the First Lady, and President Obama use their cell phones.

On January 21, 2013, I sat glued to my television and computer screens while watching the pomp and ceremony of Barack Obama's 2nd inauguration. Of all the events, I was most drawn to the inaugural parade. For about an hour, I had the pleasure of catching a unique glimpse of the family's down-to-earthiness. I also got a chance to completely geek out while watching Sasha, Malia, the First Lady, and President Obama use their cell phones.

Though this written observation is retrospective, I was able to look back at YouTube videos, Instagram and Twitter photos to notate the activities and approximate frequency with which the First Family used their mobile devices. It was fascinating to watch Sasha and Malia play on their phones. The Obama girls held their cell phone for most of the parade (which lasted roughly 1 hour long). The cell phone appeared to be an integral part of the family unit. I am reminded of Sharples, et al., discussion about cell phones in that they function as tools or “interactive agents in the process of coming to know” (pg. 7). It can be argued that this moment was a coming to know experience for the Obama girls as they snapped several pics of their mom and dad kissing, and took endearing photos of each other holding up the peace sign and making funny faces.

Perhaps the most profound takeaway from my observation is recognizing that this humanizing moment between members of the First Family, and as witnessed by the American public, was enabled by a mobile device. While watching the First Family on their cell phones, I couldn’t help but wonder what they were looking at, who they were texting, what apps were they using to edit photos, and also about the security involved in keeping the First Family and the girls’ data ‘safe and private’. I also thought about how fitting it is that Barack Obama is the first wired president in history of the United States. Since 2008, Obama’s campaign has been credited with successfully using social and mobile media for fundraising and organizing. The Obama administration prides itself on connecting with Americans using Twitter, Reddit, and Google Hangout.

While there's much to celebrate about this unique moment in techno-history, I also wonder about the cultural politics of the First Family and mobile technology. So much is to be said for the relationship between technology and its presence in the lives of vulnerable populations, particularly poor people, young girls, and people of color. The visual representation of the First Family using their cell phones illuminates conversations about what, in fact, it means for a prominent Black family with two adolescent girls to engage with mobile technology during an historical and digitally social moment. There’s much to be analyzed.

References

Sharples, M., Taylor, J., Vavoula, G. (2005). Towards a theory of mobile learning. University of Birmingham. UK.

My NCA Statement on Feminism and Communications

Due to lack of travel funds I am unable to attend NCA (National Communication Association) Conference 2012 this year. Below is my official statement that will be presented on my behalf during Saturday morning’s roundtable session entitled “Critical Perspectives on Feminism and Activism in the Third Wave”. I’ve spent the last few years grappling with feminist identity. Despite over the years having performed so-called “feminist duties” as an academic and as a political activist, (i.e. earning a MA in Women’s Studies, caucusing for Hillary Clinton in 2008, and volunteering as a hotline operator for a women’s shelter), I realize that my feminism has less to do with declaring a feminist identity and more to do with how my feminism emerges through work and scholarship, both of which almost always reflect a feminist ethic grounded in an inquiry stance. That is, I’m always questioning my-self in relation to Other; always replaying Trinh T. Minh-ha’s mystifying question in my head, “If you can’t locate the other, how are you to locate your-self?”

I worry, however, that feminism as a discipline, as a politic, as a form of activism, and as an idea(l) has become institutionalized within a western moral, ethic, and capitalistic framework that looks more and more like hierarchy, chronology, and characterized by waves (eg. generations). I also wonder about feminism as a capital enterprise. The notion of “professional feminism” troubles me. I realize folks have to make a living off of their work, but the label “professional feminist” conjures up awkward emotions. And no, I’m not referring to the welcomed contradictions of personhood that Gloria Anzaldúa brilliantly theorizes in Borderlands La Frontera, but rather I’m talking about the idea of professional feminism that exist in conflict with how I understand feminist consciousness; that is, something as sacred. Something that cannot be bought or sold. Untouched.

That said, however, I’m happy to see and feel feminist ideas spread throughout our home lives, our governments, our schools, and disseminated by way communication technologies.

To see feminist activism travel throughout time and space has been incredible to witness. With technology we are able recognize the multivalent nature of our potential of doing feminism, and by extension being feminist. Feminists have been able to spread our advocacy projects across time and space, and organize our bodies to protests in cities and neighborhoods across the globe. We have brought together domestic and international partners as we strive for justice and relief. We have called out others and at times we have had to confront ourselves. We have moved our advocacy beyond stationary online and offline spaces.

As we move throughout these spaces and places, I hope we can approach third space consciousness where we fight as much for the preservation of our selves as we fight for the preservation of others. This movement toward consciousness—born of techno advocacy practices that span across computer mediated and non-computer mediated contexts, is a threshold space of place where we can (I hope!) see ourselves through the eyes of others and by way of panoramic views.

This kind of feminism spreads like sun rays and warms me up everytime I think about it.

Feminist theory and ethnography is peppered throughout the discipline of communications. I know of researchers at my institution who look towards feminist theory and ethnography to inform their work in communications and education, and of course, I have peers who see no use for feminist theory and ethnography. In fact, they may have never heard of feminist theory and feminist ethnography throughout their academic careers. The beauty of academia and research is that we can take multiple approaches to understanding the worlds around us. As a researcher and scholar of both education and communications, I carry with me an understanding of feminist theories and methodologies that I apply to my research on media, Internet/web 2.0, and youth culture. Feminist theory and ethnography are just a few of my lenses, and I don’t expect anyone else to wear them as I do when approaching research. I do, however, expect that the discipline of communications will continue to embrace interdisciplinary approaches. I expect communication scholars to acknowledge and embrace transdisciplinary analyses informed by theoretical approaches that take into account experiences and storytelling at the intersection of gender, class, sex, sexuality, ‘race’, dis/ability, religion, tribe, and ecology.