Excerpt from my current research on #PD #mobile #youth #justice

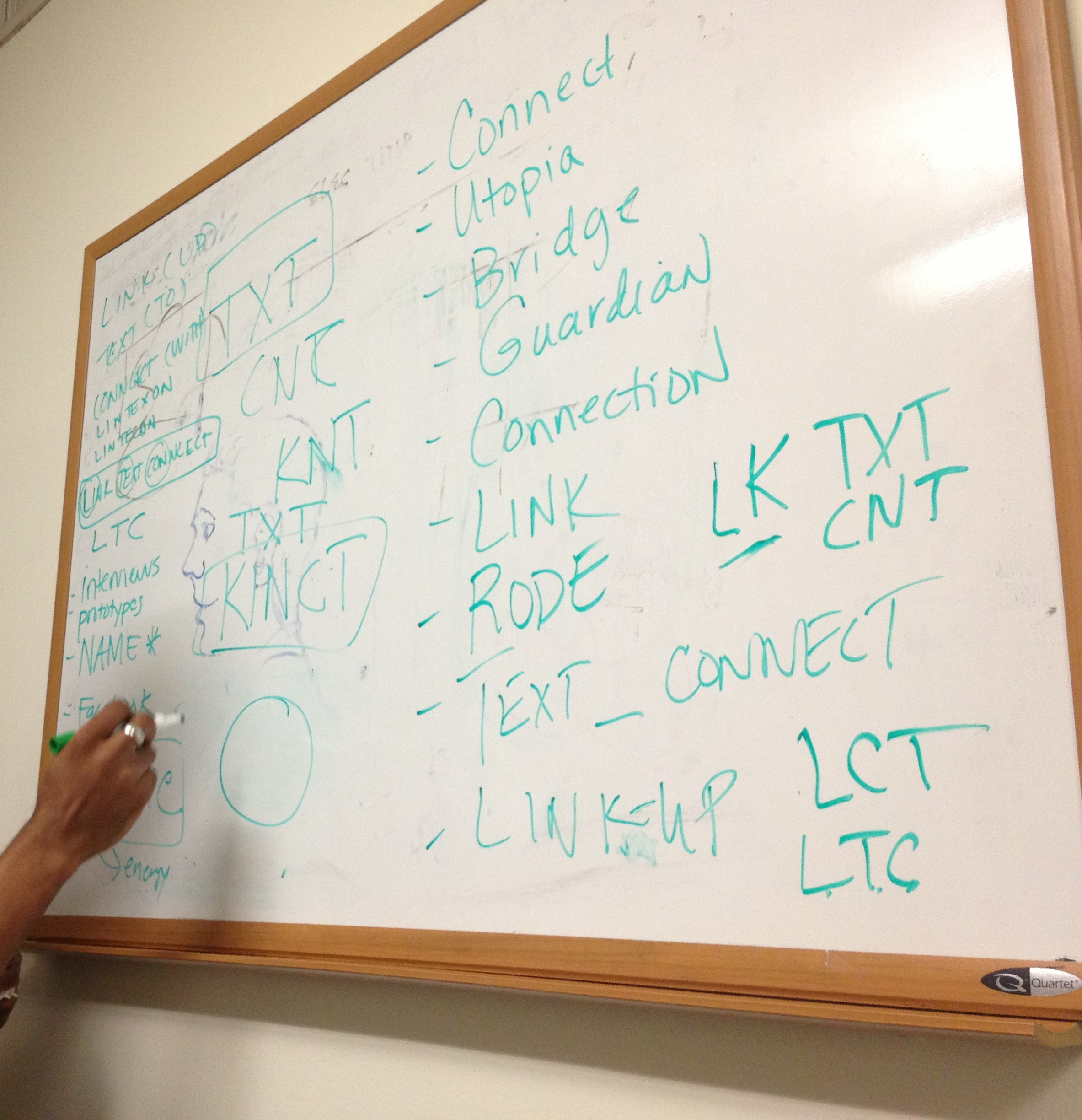

(Photo by Tara L. Conley)

The following is an excerpt from an article draft I'm currently working on about participatory design, mobile text messaging service, and court-involved youth:

During the summer of 2013 amid a controversial mayoral race in New York City[1], mayor Michael Bloomberg vetoed legislation that, in part, would create an independent inspector general to oversee the New York City Police Department (Goodman; 2013) and would allow for an expansive definition of individual identity categories under the current law. The four bills, together named the Community Safety Act (Communities United for Policing Reform; 2012), were brought forth by City Council as a result of a legal policing practice called Stop-and-Frisk. This policing practice allows New York City police officers to stop, question, and frisk citizens under reasonable suspicion of criminal activity.

While New York City residents were at odds over mayoral candidates and policing practices, young people involved in both foster care and juvenile justice systems were developing and designing a free text messaging service that would support court-involved youth in New York City to access resources and services using their cell phones. Three months before Bloomberg vetoed the Community Safety Act in New York City and while the city’s political sexting [2] scandal garnered national attention, several young people and I were discussing ways mobile technology could be used to help court-involved youth stay connected to their communities. Unaware about the extent to which Stop-and-Frisk and other safety concerns affected young people, I brought forth the idea of a text messaging platform that would primarily function as means of connecting court-involved youth to educational resources such as tutoring services and neighborhood jobs. At the time, the purpose of the platform was to create an intimate and anonymous means for young people involved in both foster care and juvenile justice systems to seek out resources beyond the institutions to which they were bound. Cell phones, I thought, would be the easiest and most comfortable way to facilitate a connection between young people and their communities.

However, the more I talked with young people, the more I understood that connecting to their communities not only meant accessing educational resources, job listings, and intervention services like hotlines, it also meant seeing the mobile device itself as a documentation tool and mobile companion for young people as they navigate the terrain of constant surveillance (Ruderman; 2013) and unstable home lives, all while trying to grasp for themselves a sense of belonging amid a psychological battlefield of metropolis dwelling [3].

Notes

[1] While running for mayor of New York City, former US congressman Anthony Weiner was involved in a national sex scandal, of which he admitted to sending sexually explicit text messages to several young women. Weiner’s indiscretions was the focal point of the NYC mayoral race and national news.

[2] Sexting is a term that describes the act of sending and receiving sexually explicit messages usually over a mobile device. The terms “sex” and “texting” began to appear in survey literature as early as 2008. Shortly thereafter the term “sexting” (a word formed by combining “sex” and “texting”) began to appear widely in academic studies and mainstream media and news (see The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy; 2008; Lounsbury, et. al.; 2011, and Ringrose, et. al., 2012).

[3] Simmel (1903) writes about the ancient polis, or city-state, as it relates to the small town. Both the city and town share an anxiety of “incessant threat” by outsiders, or enemies seen as outsiders. Simmel argues that because of this collective anxiety the environment becomes “an atmosphere of tension in which the weaker were held down and the stronger were impelled to the most passionate type of self-protection” (pg. 16). One might argue that the conditions young people experience in the city, particularly in New York City is symptomatic of an anxiety-ridden atmosphere.

References

Communities United for Policing Reform. (2012). About the Community Safety Act. Accessed on Aug. 5, 2013. Retrieved from http://changethenypd.org/about-community-safety-act

Goodman, D.J. (2013). Bloomberg vetoes measures for police monitor and lawsuits. The New York Times. Accessed on Aug. 4, 2013. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/24/nyregion/bloomberg-vetoes-measures-for-police-monitor-and-lawsuits.html?_r=0

Lounsbury, K., Mitchell, K.J., and Finkelhor, D. (2011). The true prevalence of “sexting”. Crimes Against Children Research Center. https://www.unh.edu/ccrc/pdf/Sexting%20Fact%20Sheet%204_29_11.pdf

Ringrose, J., Gill, R., Livingstone, S., Harvey, L. (2012). A qualitative study on children, young people, and ‘sexting’. NSPCC. http://www.nspcc.org.uk/Inform/resourcesforprofessionals/sexualabuse/sexting-research-report_wdf89269.pdf

Ruderman, W. (2013). To stem juvenile robberies, police trail youths before the crime. The New York Times. Accessed on Aug. 4, 2013. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/04/nyregion/to-stem-juvenile-robberies-police-trail-youths-before-the-crime.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

Simmel, G. (1903). “The Metropolis and Mental Life” translated and published in The Sociology of Georg Simmel, ed. Kurt Wolff (Glencoe, IL: Free Press, 1950), 409-424.

The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. (2008). http://www.thenationalcampaign.org/sextech/pdf/sextech_summary.pdf