On intermediaries, mediators, (im)mobilities, and proximities #RaisingDissertation

It's not easy to see things in the middle, rather than looking down on them from above or up at them from below, or from left to right or right to left: try it, you'll see that everything changes. It's not easy to see the grass in things and in words" (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987).

Before you dive in, some key terms and concepts:

(Im)mobilities - as in effects, outcomes, events. Could be understood in terms of both resources and boundaries, as having the ability to move and as being forced to stay; as effects, outcomes, events that have political significance and relevance. (See also Pellegrino, 2011).

Proximity - as in relations. Could be understood in terms of nearness, farness, togetherness, and closeness to other actors; as physical, virtual, imaginative, and communicative travel of information. (See also Bissell, 2012).

Other key concepts: near-dwellers (Bissell, 2012); near-carriers (my term, 2015); ontology of belonging; institutional and peer surveillance (Jackson, 2012).

###

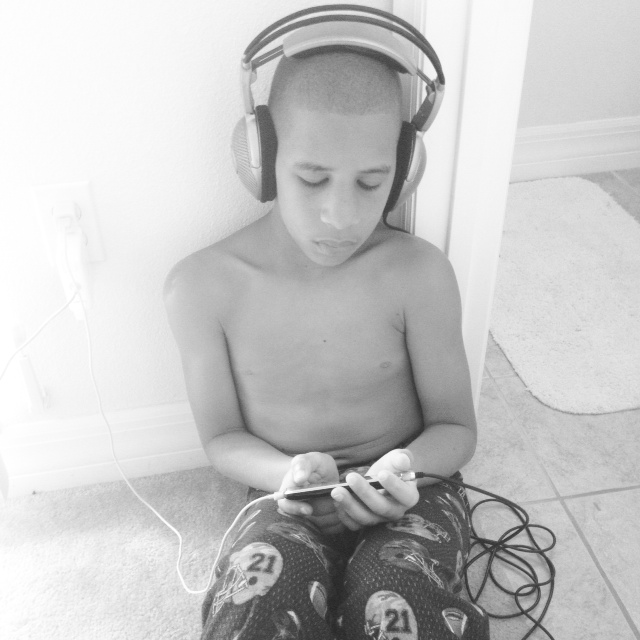

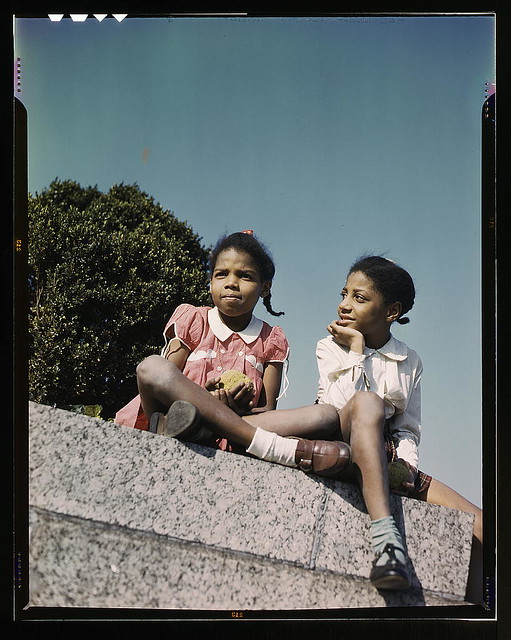

Somewhere in my literature review section might read this rumination on the everyday lives of young people, mostly Black and brown, living below the poverty line, and in-transition...

Intermediaries and Mediators

In Reassembling the Social (2005), Latour talks about the relationship between mediators and intermediaries as both human and non-human objects. Actor-Network Theory (ANT), describes an intermediary as a black box, or an object that can be viewed in terms of inputs and outputs without any knowledge of its internal workings. An intermediary, Latour writes, “transports meaning or force without transformation” (pg. 39). Mediators, unlike intermediaries, “transform, translate, distort, and modify the meaning or the elements they are supposed to carry” (pg. 39). In other words, objects that describe mediators transform meaning whereas objects that describe intermediaries do not transform.

But how do we decipher between mediators and intermediaries? For Latour, this is the first uncertainty in Actor-Network Theory; that is, whether or not objects behave as intermediaries or mediators, and it is also the source of all other uncertainties that follow.

Intermediaries and mediators lead researchers of associations into different territories. Intermediaries account for predictable outcomes, like for example, a large complex bureaucracy where objects perform repetitive and predictable tasks. Latour offers another example of an intermediary’s predictable behavior:

[A] highly sophisticated panel during an academic conference [that] may become a perfectly predictable and uneventful intermediary in rubber stamping a decision made elsewhere (pg. 39).

Mediators, unlike intermediaries are unpredictable. For example, a mediator may become complex and blow out in multiple directions like a banal conversation “where passions, opinions, and attitudes bifurcate at every turn” (pg. 39). Similar to Delueze’s rhizomatic concept, mediators point to the proliferations of objects and locates where these objects might connect to and expand toward. Mediators challenge us to follow flows rather than define containers.

ANT asks researchers of associations to treat all objects as mediators, as unpredictable and complex no matter how seemingly banal they may appear at first. This does not mean, however, that intermediaries cannot be studied nor recognized. In fact, as Latour suggests, intermediaries can become mediators and vice versa overtime. Rather than defining in advance what constitutes or makes up the social and cultural worlds we study, one approach to studying intermediaries and mediators, and their oscillating ways, is through description.

Enter: ethnography

I return now to an earlier discussion about intermediaries behaving in predictable ways. To further elaborate on the application of intermediaries in this research, I sought out other works aside from ANT and social theory where the concept of intermediaries was applied.

Yannakakis’ ethnohistorical study The Art of Being In-between (2008) explores indigenous resistance and colonial intermediaries of Sierra Norte of Oaxaca, a region of colonial Mexico. In Yannakakis work, we learn about native intermediaries, or those who “by virtue of their legitimacy among native peoples [helped to] administer colonial society” (pg. 2). Yannakakis’ study follows the trajectory of social rebellions and the rise of colonial intermediaries that became martyrs and some who were eventually declared saints centuries after their deaths. This ethnohistory provides another perspective about the ways intermediaries, in this case human actors, transport meaning from one group (natives) to another group (political elites). When citing Daniel Richter’s work on network theory and cultural brokers in the seventeenth-century (a concept synonymous with Yannakakis’ application of intermediaries), Yannakakis writes:

[Cultural brokers’] position in multiple networks and coalitions meant that they were both varyingly situated and not situated at all; they occupied an ‘intermediate position, one step removed from final responsibility in decision making [...] Participating in social networks from an intermediate position required not only considerable communicative skills but also a ‘tactical’1 sensibility (pg. 10).

Yannakakis applies the concept of intermediaries somewhat differently than Latour does in Reassembling. Throughout In-between, Yannakakis refers to intermediaries as bridges and brokers or those that “played a considerable role in connecting the colonial state to localities” (pg. 33). Yannakakis implies a bidirectional transfer of meaning (what goes through comes back) whereas Latour’s illustration of intermediaries depicts a unidirectional model of transfer (what goes in come out). However, where Yannakakis and Latour’s concept of intermediaries intersect is in how the transfer of meaning moves; that is, in predictable ways.

It is at this intersecting point in Latour and Yannakakis’ analyses that I enter into a discussion about the proximities (or relations) between human actors (near-dwellers) and non-human actors (near-carriers) as mediators and intermediaries, and how these proximities might constitute young peoples’ (im)mobilities.

Enter: a study of (im)mobilities and proximities in the lives of ‘disconnected’ youth

Through a mapping of (im)mobilities and proximities, I construct a visual representation of relations and events between research participants, technologies, institutions, as well as locate assemblages, entanglements, ruptures, flows, and discontinuities therein. Stripped of the abstract, this work essentially constitutes a story of everyday life for teens and young adults grappling with where and how to belong; when to stay, how to leave, when to log on, how to search, when to watch, and how to recognize when one is being surveilled. It is also a story about the politics of nearness and distance and how power relations are constantly reshaped between young people, key adults in their lives, unanticipated neighbors, police officers, technologies, and institutions.

My argument in this work goes without saying: Disconnected youth are far from disconnected. In fact, they dwell near, within, and among people, places, and things in foreseen and unexpected ways. For young people in transition from adolescence to adulthood, where they exist “in-between” jobs and schooling, their experiences also constitute paradoxical encounters. Where belonging on the block meets suspicion in the neighborhood, where animosity in the projects meets ambivalence in the city, where support at the cafe meets uncertainty at school, where curiosity online meets disinterest offline, where loss at home meets hope for the future. When blown a part these encounters reveal an apparatus of always-becoming, of always-in between.

###

Currently reading:

Bissell, D. (2012). Pointless mobilities: Rethinking proximity through the loops of neighbourhood. Mobilities, 8 (3), 349-367.

Fassin, D. (2015). Enforcing order: An ethnography of urban policing. Cambridge, MA: Polity Press.

Goffman, A. (2014). On the run: Fugitive life in an American city. New York, NY: Picador.

Lewis-McCoy, R.L. (2014). Inequality in the promised land: Race, resources, and suburban schooling. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Pellegrino, G. (2011). Studying (im)mobility through a politics of proximity. In G. Pellegrino, ed. The politics of proximity, 1-14. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Further reading:

Sheller, M. & Urry, J. (2012). Mobile technologies of the city. Routledge.

Urry, J. (2007). Mobilities. Polity Press.

Urry, J. (2002). Mobility and proximity. Sociology, 36 (2), 255-274.

Urry, J. (2000). Sociology beyond societies: Mobilities for the twenty-first century. Routledge.

Never stopped reading:

Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

1 I apply Yannakakis’ definition here: “‘Tactics’ are the subtle, everyday actions undertaken by individuals to navigate, resist, and subvert authority” (pg. 33).

Fieldnotes 2: "In New York City, you have to make your own space"

The following are excerpts from my fieldnotes describing a recent site visit. The names have been changed to protect privacy.

The following are excerpts from my fieldnotes describing a recent site visit. The names have been changed to protect privacy.

Excerpt 1

Roughly 45-minutes into the three hour visit, I noticed something interesting happening. This wasn’t anything I hadn't seen or read about before. It was certainly an instance that I’ve witness emerge inside and outside of classroom spaces, at public events, and around the dinner table. As Chad, a frequent customer at the cafe, talked to me, I noticed behind the counter that Ethan, Ben, and another young man who worked there were all hunched over their cell phones. iPhones, to be exact.

“Yo, you didn’t tag me, son!” Ethan said to Ben. There weren’t any customers in the cafe at this point. Ethan and Ben, while sitting behind the counter, were looking at their phones toggling through Instagram photos.

“Yo, she is ugly, son!” Ethan said to Ben, laughing. Chad looked up from our conversation and asked who they were looking at.

“That’s wifey.” Ethan responded looking at the iPhone screen.

“His wifey is ugly? How’s that?” Chad asked.

“No, no,” Ethan replied, “We looking at another picture now.”

If the cafe was a gendered space, it couldn’t be anymore masculinist than it was at this particular moment. This is what being in a barbershop must feel like, I thought to myself. I was the only woman in the space but that didn’t stop Ethan, Ben, and Chad from exchanging banter about pics of girls and women they gawked at on Instagram. These were light moments between Ethan, Ben, and Chad. I didn’t interject.

Later in the conversation, I asked Ethan and Ben if they were on Twitter.

“Nah,” replied Ethan.

They preferred Instagram along with a new Instagram-like application called Shots.

“Twitter is for females.” Chad interjected. “It’s gossipy, you know?”

“And Instagram isn’t?” I responded. (I had to.)

“Instagram is messy, but not gossipy like Twitter.” Chad replied.

We spent the next fifteen minutes talking about Twitter, Instagram, and then Facebook--which everyone, even me, seemed to agree was wack.

“People break up over Facebook, yo!” Ethan announced.

He told me about the time his girlfriend saw that he liked another girl’s picture on Instagram.

“I was liking this girl's pic to get more followers. It’s like promotion.” He said.

When Ethan's girlfriend found out that he was liking other girl's pictures on Instagram, she ended the relationship.

“I didn’t even do nothing!” He said.

Ben, who at this point I’ve dubbed the quiet one (relative to Ethan), asked if I was on Instagram. I told him I was, but that my account is private. I told him that I’m more active on Twitter. It’s where I get my news.

“Twitter used to be hot back in the day when it first came out, but not anymore.” Ethan said.

In many ways, I agreed with him. Twitter is a much more difficult space to navigate these days than in previous years. But perhaps so is social media in general.

Ethan showed me a picture of him on Instagram when he was 15-years-old. Ben posted the photo but forgot to tag Ethan. If Ethan wasn’t sitting directly next to Ben while they were scrolling through pictures, he probably wouldn't have noticed that Ben didn’t tag him.

“Can I take a picture of you guys while you're looking at your phones?” I asked.

Ethan eyes lit up. “Yes! You gonna put it on Instagram?”

I told Ethan and Ben that I would never post their pictures on Instagram. I also told them that the photos I was taking throughout the day were only going to be used for research.

But Ethan persisted. “You can put [the pic] on Instagram if you want.”

I didn't. Instead, I texted the photos to Ethan's cell phone.

These young men, although labeled disconnected at one point in their lives, were anything but. They moved about in the physical space of the cafe. They also moved about in the virtual spaces of social media. Their bodies, identities, and constructs moved fluidly across time and space. Sociality manifested as mobilities within and among physical, virtual, online, and offline spaces (or places?). These movements, constructs, activities, or whatever you call it were indicative of two very connected and co-present people.

Ethan and Ben's iPhones played significant roles in how connection was established and maintained. These objects, in other words, sustained connection. They also remained in Ethan and Ben's pockets the entire time while they served customers coffee and food.

Yet, Ethan and Ben clearly chose when and where to connect. While they sat in the physical space of the cafe--a constant, sustaining, and perhaps even safe place--the virtual spaces they participated in via their iPhones were not on equal footing. To Ethan and Ben, the spaces that constitute social media held different meanings about their interactions with other people.

Excerpt 2

Later on that day, Patrick, a white guy and regular customer arrived. He playfully argued with Ethan saying that Samsung makes better phones and electronics than does Apple. Ethan wasn’t hearing it though. He, and I too, pointed out how the Apple brand is much more sophisticated than Samsung.

"But, then again," I interjected, “neither Apple nor Samsung are paying my bills so for me it’s not that serious.” I said this while pulling out my iPad Air to check my email.

The banter continued. It was a lovely indication and reminder that there was community here, and it was alive, emerging, and always-becoming.

The topic of conversation shifted. I found out that Patrick was once a middle school teacher. He lived in the neighborhood. Patrick talked about once working in rural North Carolina. He loved the students but hated the parents. He chose to quit teaching once he realized he wasn’t being supported.

Patrick then talked about how it was too expensive to live in Bed-Stuy.

“You can’t find a studio in this neighborhood for less than $1100,” he said.

“Shit, if that!” Chad interjected.

Patrick continued, “The Hassidics are buying up the blocks around here. Then, you know what they do? They rent out rooms. Not apartments. Rooms! You end up living in a shoebox for thousands of dollars.”

“Yeah, that’s pretty crazy” I replied.

“In New York City, you have to make your own space,” Patrick said.

Space, an enigmatic concept, seems to facilitate and impede connection all at once, doesn't it? How then do we make spaces when, in our own lives, space is so obviously scarce, devalued, contested, and always-becoming?

My Dissertation Bibliography

My dissertation work constitutes a mixed-method study that explores the networked lives of teens and young adults who are characterized as disconnected, vulnerable, or in-transition. I unpack the concept of disconnection, in particular, and explore with young people what it means for them to be connected, mobile, and supported, and how they communicate the experience of connection, mobility, and support through various physical and virtual constructs of place.

My dissertation work constitutes a mixed-method study that explores the networked lives of teens and young adults who are characterized as disconnected, vulnerable, or in-transition. I unpack the concept of disconnection, in particular, and explore with young people what it means for them to be connected, mobile, and supported, and how they communicate the experience of connection, mobility, and support through various physical and virtual constructs of place.

The following bibliography is alive and constantly expanding:

References

Anzaldúa, G. E. and Keating, A. (eds). (2002) this bridge we call home: radical visions for transformation. New York: Routledge.

Anzaldúa, G. E. (1987). Borderlands la frontera: The new mestiza. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books.

Altheide, D.L. (1996). Qualitative media analysis. Sage Publications.

American Public Transportation Association (2014). Millennials and mobility: Understanding the millennial mindset. Report.

Bambina, A. (2007). Online social support: The interplay of social networks and computer-mediated communication. New York: Cambria Press.

Banks, D. (2014, Jan 31). #Review Actor-Network Theory’s approach to agency. Retrieved from http://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2014/01/31/review-actor-network-theorys-approach-to-agency/.

Banks, D. (2011, Dec. 2). A brief summary of Actor Network Theory. Retrieved from http://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2011/12/02/a-brief-summary-of-actor-network-theory/.

Baumgartner, J., & Buchanan, T. (2010). ‘‘I have HUGE stereotypes’’: Using eco-maps to understand children and families. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 31(2), 173–184.

Baumgartner, J., Burnett, L., DiCarlo, C. F., and Buchanan, T. (2012). An inquiry of children’s social support networks using eco-maps. Child Youth Care Forum, 41, 357-369.

Berkman, L. F., and Breslow, L. (1983). Health and ways of living: The Alameda county study. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bernard, H. R. (1994). Research methods in anthropology: qualitative and quantitative approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Besharov, D.J. (1999). America’s disconnected youth: Toward a preventative strategy. Washington, D.C.: Child Welfare League of America.

Bødker, S. and Grønbæk, K. (1991). Cooperative prototyping: Users and designers in mutual activity. International Journal of Man/Machine Studies. 34 (3), 453-478.

Bork, R. H. (2012). From at-risk to disconnected: Federal youth policy from 1973-2008 (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest, UMI Dissertations Publishing. (3505118)

Borgatti and Lopez-Kidwell (2011). Network theory. In The Sage Handbook of Social Network Analysis, Scott, J. and Carrington, P.J. (Eds), pp. 40-54. London: Sage.

boyd, d. (2014). It’s complicated: The social lives of networked teens. Connecticut: Yale University Press.

boyd, d. (2011). "Networked Privacy." Personal Democracy Forum. New York, NY, June 6.

boyd, d. (2012). “White flight in networked publics? How race and class shaped American teen engagement with Myspace and Facebook” in Race After the Internet, Nakamura, L. and Chow-White, P. (Eds), pp. 203-222. New York: Routledge.

boyd, d. (2008). Why youth <3 social network sites: The role of networked publics in teenage social life. In D. Buckingham (Ed.), Youth, identity, and digital media (pp. 119–142). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

boyd, d. m., & Ellison, N. B. (2007). Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(1). Retrieved November 24, 2009, from http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol13/issue1/boyd.ellison.html.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). Contexts of child rearing: Problems and prospects. American Psychologist, 34, 844–850.

Burnett, L. (2008). Measuring children’s social support networks: Eco-mapping protocol. (master’s thesis). Retrieved from Louisiana State University Electronic Thesis & Dissertation Collection.

Business Innovation Factory (2013). If I could make a school. A student-driven participatory design studio to re-imagine education. Report.

Cairns, R., Leung, M., Buchanan, L., & Cairns, B. (1995). Friendships and social networks in childhood and adolescence: Fluidity, reliability, and interrelations. Child Development, 66, 1330-1345.

Caplan, G. (1974). Support systems and community mental health. In Support systems, G. Caplan (ed.), 1-40. New York: Behavioral Publications.

Cassel, J. (1976). The contributions of the social environment to host resitance/ American Journal of Epidemiology, 104, 107-122.

Castells, M. (1996). The space of flows. In The Rise of the Network Society (pp. 407-460) Oxford: Wiley.

Castells, M. (1999). The social implications of Information and Communication Technologies. In The world social science report (236-245). Paris: UNESCO.

Chaiken, J., Dosa, S., Dungan, S., and Silberstein, S. (Producers), & Kornbluth, J. (Director). (2013). Inequality for all [Motion picture]. United States: 72 Productions.

Chetty, R., Hendren, N., Kline, P., Saez, E. (2014). Where is the land of opportunity? The geography of intergenerational mobility in the United States. Report. Retrieved from http://obs.rc.fas.harvard.edu/chetty/mobility_geo.pdf.

Chua, V., Madej, J. and Wellman, B. (2011). Personal communities: The world according to me. In The Sage Handbook of Social Network Analysis, Scott, J. and Carrington, P.J. (Eds), pp. 101-115. London: Sage.

Chun, W. H. K. (2012). “Race and/as technology or how to do things to race” in Race After the Internet, Nakamura, L. and Chow-White, P. (Eds), pp. 38-60. New York: Routledge.

Cobb, S. (1976). Social Support as a Moderator of Life Stress. Psychosomatic Medicine, 38, 300-314.

Conley, T. L. (2013, December 16). Tracing the impact of online activism in the Renisha McBride case. [Web Log Post]. Retrieved from http://www.mediamakechange.org/blog/2013/tracing-the-impact-of-online-activism-in-the-renisha-mcbride-case

Conley, T.L. (2007, November). Virtual volunteers: Hurricane Katrina’s impact and women’s resolve. [Web Log Post]. Retrieved from http://www.taralconley.org/featured-articles-archive/virtual-volunteers-hurricane-katrinas-impact-and-womens-resolve/

Cortesi, S., Haduong, P., & Gasser, U. (2013). Youth news perceptions and behaviors online: how youth access and share information in a Chicago community affected by gang violence. Berkman Center for Internet & Society. Retrieved January, 25, 2014 from http://ssrn.com/

Csikszentmihalyi, M. 1993. “Why We Need Things.” In History from Things (edited by S. Lubar & W.D. Kingery), Smithsonian Institution Press.

Digital Harlem (2010). Everyday life 1915-130. Retrieved from http://heur-db-pro-1.ucc.usyd.edu.au/HEURIST/harlem/

Dinerstein, J. (2006). Technology and its discontents: On the verge of the posthuman. American Quarterly, 58(3), 569-595.

Disconnect. (2014). Disconnect. Retrieved from https://disconnect.me/#about

Dreamact.info. (2010). Dream Act portal. Retrieved from http://dreamact.info/

Duggan, M. and Smith, A. (2014). Social media update 2013. Available at: http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Social-Media-Update.aspx.

Erickson, B. (2004). The distribution of gendered social capital in Canada. In Henk Flap and Beate Volker (Eds.), Creation and Returns of Social Capital. New York: Routledge, pp. 27-50.

Fouché, R. (2012). “From black inventors to one laptop per child: Exploring a racial politics of technology” in Race After the Internet, Nakamura, L. and Chow-White, P. (Eds), pp. 61-83. New York: Routledge.

Fu, Y. C. (2008). Position generator and actual networks in everyday life: An evaluation with contact diary. In Nan Lin and Bonnie H. Erickson (Eds.), Social Capital: An International Research Program. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 49-64.

Fu, Y.C. (2007). "Contact Diaries: Building Archives of Actual and Comprehensive Personal Networks". Field Methods, 19, pp. 194-217.

Fu,Y., 2004. Network closure and expressive returns on time investment in social interactions: Evidence from 52 contact diaries. Paper presented at the International Conference on Social Capital: Communities, Classes, Organizations, and Social Networks, Taichung, Taiwan, December 13–14.

Fernandes-Alcantara, A.L. (2012a). Vulnerable youth: Background and policies. Congressional Research Service. Report.

Fernandes-Alcantara, A.L. (2012b). Youth and the labor force: Background and trends. Congressional Research Service. Report.

Fernandes, A.L. and Gabe, T. (2009). Disconnected youth: A look at 16- to 24-year olds who are not working or in school. Congressional Research Service. Report.

Floyd, Christiane (1984) A systematic look at prototyping, In R. Budde (ed.), Approaches to prototyping, Proceedings of the Working Conference on Prototyping. Berlin: Springer, 1-18.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: The Continuum International Publishing Group, Inc.

Gray, M. (2009). Out in the country: Youth, media, and queer visibility in rural America. New York: New York University Press.

Greenhow, C., & Robelia, B. (2009). Informal learning and identity formation in online social networks. Learning, Media and Technology, 34(2), 119–140. Gruber, D. (Ed.). Introduction in social network analysis: Theoretical approaches and empirical analysis with computer-assisted programmes [PowerPoint document]. Retrieved from Academia Online Web site: https://www.academia.edu/4072066/Dr_Denis_Gruber_Introduction_in_Social_Network_Analysis.

Guggenheim, M. (2013). The long history of prototypes. Retreived from http://limn.it/the-long-history-of-prototypes/.

Haraway, D. (1991). “A cyborg manifesto: Science, technology, and socialist-feminism in the late twentieth century," in Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, pp. 149-181. New York: Routledge.

Harvey, D. (1996). Social justice and the geography of difference. London: Blackwell.

Horst, H. (2011). Free, social and inclusive: Appropriation of new media technologies in Brazil. International Journal of Communication, 5, 437-462.

Irish, L. (2014, May 12). Summit calls for getting ‘disconnected youth’ back to school. AZ Ed News. Retreived from http://azednews.com/2014/05/12/summit-calls-for-getting-disconnected-youth-back-to-school/

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide. New York. New York University Press.

Jenkins, H. (2009). Confronting the challenges of participatory culture: Media education for the 21st century

Keating, A. (Ed). (2005). EntreMundos/among worlds: New perspectives on Gloria Anzaldúa. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Keenan, E. K. and Miehls, D. (2008). Third space activities and change processes: An exploration of ideas from social and psychodynamic theories.” Clinic Social Work Journal. 36, 165-175.

Kim, S.D. (2002). “Korea: Personal meanings.” In J.E. Katz and M. Aakhus (Eds.), Perpetual contact: Mobile communication, private talk, public performance (pp. 63-79). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Krempel, L. (2011). Network visualization. In The Sage Handbook of Social Network Analysis, Scott, J. and Carrington, P.J. (Eds), pp. 558-577. London: Sage.

Kress, G. (2003). Literacy in the new media age. New York, NY: Routledge.

Kress, G. and Van Leeuwen, T. (2001). Multimodal discourse: The modes and media of contemporary communication. Hodder Arnold Oublication.

Latour, B. (2014). Agency at the time of the anthropocene. New Literary History, 45(1), 1-18.

Latour, B. (2005). Resembling the social: An introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford Press.

Latour, B. (1993). We have never been modern. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Latour, B., Woolgar, S., and Salk, J. (1986). Laboratory life: The construction of scientific facts. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Law, J. (2007). Actor Network Theory and material semiotics. Retrieved from http://www.heterogeneities.net/publications/Law2007ANTandMaterialSemiotics.pdf.

Leander, P., Phillips, C., & Taylor, K.H. (2010). The changing social spaces of learning: Mapping new mobilities. Review of Research in Education, 34, 329-394.

Leander, K. & Vasudevan, L. (2009). Multimodality and mobile culture. In C. Jewitt (Ed.) Handbook of multimodal analysis. (pp. 127-139). London: Routledge.

LeCompte, M.D. and Preissle, J. (1993). Ethnography and qualitative design in educational research. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

LeCompte, M. D. and Schensul, J. J. (1999). Designing & conducting ethnographic research. Walnut Creek, Calif.: AltaMira Press.

Lesko, N (2012). Act your age: A cultural construction of adolescence. London: Routledge.

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space (D. Nicholson-Smith, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Leone, P. & Weinberg, L. (2010). Addressing the unmet educational needs of children and youth in the juvenile justice and child welfare systems. Center for Juvenile Justice Reform. Georgetown University. Report.

Lerner, J., Lubbers, J.M., Molina, J.L. and Brandes, U. (2014). Social capital companion: Capturing personal networks as they are lived. Grafo. 3,18-37.

Lim, S., Chan, Y., Vadrevu, S., Basnyat, I. (2012a). Managing peer relationships online: Investigating the use of Facebook by juvenile delinquents and youths-at-risk. Computers in Human Behavior, 29, 8-15.

Lim, S., Vadrevu, S. Hian, Y., Basnyat, I. (2012b). Facework on Facebook: The online publicness of juvenile delinquents and youths-at-risk. Journal of of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 56(3), 346-361.

Lin, N. and Erickson, B. (2008). Theory, measurement, and the research enterprise on social capital. In Nan Lin and Bonnie H. Erickson (Eds.), Social Capital: An International Research Program. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 1-24.

Lindström, L. (2012). Youth, participation, leisure and citizenship. The Open Social Science Journal, 5, 1-14.

MaCurdy, T., Keating, B., Navagarapu, S.S. (2006). Profiling the plight of disconnected youth in America. Report.

Manes, Claire [intensetweeting]. 2014, April 10). @classynogin @MHarrisPerry @hashtagfeminism Brought us together, felt less alone. It would be prejudicial if SM influenced court cases! [Tweet]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/intensetweeting/status/454297043507216384

Mastin, Metzger, Golden (2013). Foster care and disconnected youth.

McCormick, K., Stricklin, S., Nowak, T., & Rous, B. (2005). Using eco-mapping as a research tool. National Early Childhood Transition Center.

McDermott, R. and Varenne, H. (1995). Culture “as” disability. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 26(3), 324-348.

Marin and Wellman (2011). Social network analysis: An introduction. In The Sage Handbook of Social Network Analysis, Scott, J. and Carrington, P.J. (Eds), pp. 11-25. London: Sage.

MDRC (2014). Building knowledge to improve social policy. http://www.mdrc.org/ Date accessed April 29, 2014.

Measure of America, (2012). One in seven: Ranking youth disconnection in the 25 largest metro areas. Report. http://www.measureofamerica.org/one-in-seven

Mitchell, J.C. (1969). Social networks in urban situations: Analyses of personal relationships in central Africa. Manchester University Press.

Mizuko, I., Baumer, S., Bittanti, boyd, d., M., Cody, R., Herr, B., Horst, H. A., Lange, P. G., Mahendran, D., Martinez, K., Pascoe, C. J., Perkel, D., Robinson, L., C. Sims, C., and Tripp, L. (2008). hanging out, messing around, geeking out: Living and Learning with New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Mulcahy, D. (2012). Affective assemblages: body matters in the pedagogic practices of contemporary school classrooms. Pedagogy, Culture & Society 20(1), 9-27.

Osgood, W. D., Foster, M. E., & Courtney, M. E. (2010). Vulnerable populations and the transition to adulthood. The Future of Children, 20(1), 209-229.

Osgood, W. D., Foster, M. E., Flanagan, C., & Ruth, G. R. (Eds.). (2007). On your own without a net: The transition to adulthood for vulnerable populations. Chicago, IL: University Of Chicago Press.

Pateman, C. (1970). Participation and democratic theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Peterson, S.B. (2010). Examining the referral stage for mentoring high-risk youth in six different juvenile justice settings. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Report.

Pew Research (2010). Millennials: Confident. Connected. Open to change. Report. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2010/02/24/millennials-confident-connected-open-to-change/.

Pew Internet (2011). Social networking sites and our lives http://www.pewinternet.org/2011/06/16/social-networking-sites-and-our-lives/.

Pica-Smith, C. and Veloria, C. (2012). “At risk means a minority kid:” Deconstructing deficit discourses in the study of risk in education and human services. Pedagogy and the Human Sciences, 2(1), pp. 33-48.

Potts, L. (2014). Social media in disaster response. How experience architects can build for participation. New York: Routledge.

Powell, K. (2010). Making sense of place: Mapping as a multisensory research method, 16(7), 539-555.

Puar, J (2011). ‘I would rather be a cyborg than a goddess’: Intersectionality, assemblage, and affective politics. European Institute for Progressive Cultural Politics. Retrieved from http://eipcp.net/transversal/0811/puar/en.

Quinlan, A. (2012). Imagining a feminist Actor-Network Theory. International Journal of Actor-Network Theory and Technological Innovation, 4(2), 1-9.

Ray, R. A., & Street, A. F. (2005). Eco-mapping: an innovative research tool for nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 50(5), 545-552.

Reid, S.A. (2013). Institutional friendship: Exploring the egocentric networks of incarcerated youth. Dissertation.

Restivo, S. (2010). Bruno Latour: The once and future philosopher. In The New Blackwell Companion to Major Social Theorists. Ritzer, G. and Stepinsky, J. (Eds.), 1-39. Boston: Blackwell.

Ringrose, J. 2011. Beyond discourse? Using Deleuze and Guattari’s schizoanalysis to explore affective assemblages, heterosexually striated space, and lines of flight online and at school. Education Philosophy and Theory 46: 598–618.

Roberts, S. (2011). Beyond ‘NNET’ and ‘tidy’ pathways: considering the ‘missing middle’ of youth transition studies. Journal of Youth Studies, 14(1), 21-39.

Robertson, S. (2009). Fuller Long: A teenager’s life in Harlem [Web blog post]. Retrieved April 17, 2014, from http://digitalharlemblog.wordpress.com/2009/04/17/fuller-long/.

Robertson, S., White, S., and Garton, S., (2013). Harlem in black and white: Mapping Race and place in the 1920s. Journal of Urban History, 39(5), pp. 864-880.

Robertson, S., White, S., and Garton, S., and White, G. (2010). This Harlem life: Black families and everyday life in the 1920s and 1930s. Journal of Social History. 44(1), pp. 97-122.

Rousseau, J.J. (1968). The social contract. Penguin Books.

Russell, A., Ito, M., Richmond, T., and Tuters, M. (2008). Culture: Media convergence and networked participation. In Networked Publics, K. Varnelis (Ed), pp. 43-76. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Sayes, E. (2014). Actor-Network Theory and methodology: Just what does it mean to say that nonhumans have agency? Social Studies of Science, 44(1), 134-149.

Schaffer, S. (1991). From the sacred to the sacred object: Girard, Serres, and Latour on the ordering of the human collective. Techné: Research in Philosophy and Technology 16(2), 105-122.

Shackleford, S.L. [Shae-Lee Shackleford]. 2013, July 2. The anti-social network – short film. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e0H6AzEMHSc

Silva, D. (2013). Undocumented youth use the Internet and social media for info and support. Pavement Pieces. Retrieved from http://pavementpieces.com/undocumented-youth-use-the-internet-and-social-media-for-info-and-support/

Söderström, S. (2009). Offline social ties and online use of computers: A study of disabled youth and their use of ICT advances. New Media & Society, 11(5), 709-727.

Song, L., Son, J., Nin, L. (2011) Social support. In The Sage Handbook of Social Network Analysis, Scott, J. and Carrington, P.J. (Eds), pp. 116-128. London: Sage.

Stald, G. (2008). Mobile identity: Youth, identity, and mobile communication media. In D. Buckingham (Ed.), Youth, Identity, and Digital Media (pp. 143-164). The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Media and Learning. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. doi: 10.1162/dmal.9780262524834.143.

Task Force on Education of Young Adolescents. (1989). Turning points: Preparing American youth for the 21st century. New York, NY: Carnegie Council on Adolescent Development.

The City of New York (2014). Young adult internship program. Retrieved from http://www.nyc.gov/html/dycd/html/jobs/internship.shtml.

The William T. Grant Foundation Commission on Work Family and Citizenship. (1988). The Forgotten Half: Pathways to Success for America's Youth and Young Families. Washington, DC: Author.

Turk, G. [Gary Turk]. 2014, April 25. Look up. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z7dLU6fk9QY

Turkle, S. (2012a). Alone together: Why we expect more from technology and less from each other. New York: Basic Books.

Turkle, S. (2013). The documented life. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/12/16/opinion/the-documented-life.html

Turkle, S. (2012b). The flight from conversation. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/22/opinion/sunday/the-flight-from-conversation.html?pagewanted=all&_r=1&

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2014). Concept and history of permanency in the U.S. child welfare. https://www.childwelfare.gov/permanency/overview/history.cfm. Accessed on April 16, 2014.

Valentine, G., & Holloway, S. L. (2002). Cyberkids? Exploring children’s identities and social networks in on-line and off-line worlds. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 92(2), 302–319.

Van Blerk, L. (2005). Negotiating spatial identities: Mobile perspectives on street life in Uganda. Children’s Geographies, 3, 5–21.

van der Gaag, M. and Snijders, T.A.B (2005). The resource generator. Social Networks 27: 1-27.

van der Gaag, M. Snijders, T.A.B., and Flap, H. (2008). Position generator measures and their relationship to other social capital measures. In Nan Lin and Bonnie H. Erickson (Eds.), Social Capital: An International Research Program. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 27-48.

Varnelis, Kazys, ed. 2008. Networked Publics. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Varnelis, K. and Friedberg, A. (2008). Place: The networking of public space. In Networked Publics, K. Varnelis (Ed), pp. 15-42. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Visweswaran, K. (1994). Defining feminist ethnography. In K. Visweswaran (Ed.), Fictions of Feminist Ethnography (pp. 17-39). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Walker, (2012). When gangs were white.

Watt, P., & Stenson, K. (1998). The street: “It’s a bit dodgy around here”: Safety, danger, ethnicity and young people’s use of public space. In T. Skelton & G. Valentine (Eds.), Cool places: Geographies of youth cultures (pp. 249–265). London: Routledge.

Wenger, Etienne. 1998. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge, UK, and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Williams, P. (2005). What is social support?: A grounded theory of social interaction in the context of the new family. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from Citation Online. http://hdl.handle.net/2440/49476.

Fieldnotes 1: First Site Visit

(Source)

The following are excerpts from my field notes describing a recent site visit. The names have been changed to protect privacy.

Excerpt 1

I approached the counter where I saw two young Black men standing behind the food preparation station making fruit drinks and coffee. As I waited for one of the young men to take my order, I looked around the Cafe and saw pinned to the wall several Polaroid photos. In all of the photos appeared Father Tim posing with who I assumed were famous people that visited the Cafe conveniently located in the Brooklyn neighborhood made famous by its native son, Shawn “Jay Z” Carter. Just a few blocks north of the Cafe stood Marcy Projects, the once home of the now uber famous Brooklyn rapper.

As I stood there gazing at the photos, Juan, who accompanied me to the site visit, tapped me on the shoulder and pointed to a giant framed photo of Jay Z sitting with his hands folded and looking off into the distance somewhere. I thought maybe the photographer caught Jay Z thinking about how far he’d come since Marcy. On the upper left hand side of the photo was Jay Z’s autograph scribbled in blue. The photo was a prominent fixture in the Cafe. It hung directly across from the young Black man preparing my coffee.

(Source)

Excerpt 2

After our chat, Father Tim and I walked out of the Cafe to meet back up with Juan who was standing outside waiting for us. We talked outside for another hour. We chatted about the neighborhood and the serious social issues facing young Black and brown men. We laughed too.

“Is Harlem turning white like Brooklyn?” Father Tim asked.

He was aware not only of the economic issues facing his neighborhood but also of the racial demographics affecting the entire New York City metropolitan area. Here, I thought, was this Irish priest lamenting about white gentrification, and mincing no words.

He got it.

Three-thirty approached, and if I was ever going to make it back to Harlem by 5 o’clock, I had to prepare for my trek back uptown. We said our goodbyes and Juan and I headed for the G train.

I left the Cafe feeling like I made a new friend, and reassured that a community would have me.

Prologue to the Research #RaisingDissertation

#RaisingDissertation is a way to keep me sane and connected to the outside world while working, at times in isolation, on my dissertation research. From time to time, and depending on my mood, I will post draft excerpts from my dissertation research to this public blog. I welcome dialogue from subscribers, readers, and lurkers. I acknowledge that ideas belong to the universe. That said, however, if you wish to write about my research elsewhere, you must cite my work here. For those in the press reporting about the media and technology uses among 'disconnected' youth, and youths involved in foster care and juvenile justice systems, feel free to contact me directly. I'd love to share my research with you; this should not to be confused with doing your research for you. For others researching in this area, I also welcome your insights here. As always, I'm happy to connect.

The following is an excerpt from an ever-growing dissertation involving the mediated lives of vulnerable or 'disconnected' youth in New York City.

#RaisingDissertation is a way to keep me sane and connected to the outside world while working, at times in isolation, on my dissertation research. From time to time, and depending on my mood, I will post draft excerpts from my dissertation research to this public blog. I welcome dialogue from subscribers, readers, and lurkers. I acknowledge that ideas belong to the universe. That said, however, if you wish to write about my research elsewhere, you must cite my work here. For those in the press reporting about the media and technology uses among 'disconnected' youth, and youths involved in foster care and juvenile justice systems, feel free to contact me directly. I'd love to share my research with you; this should not to be confused with doing your research for you. For others researching in this area, I also welcome your insights here. As always, I'm happy to connect.

The following is an excerpt from an ever-growing dissertation involving the mediated lives of vulnerable or 'disconnected' youth in New York City.

Prologue to the Research

While I was completing a master’s degree in Women’s Studies I spent long hours in my room reading and writing about people dislocated from their communities as a result of natural disaster and social conflict. Also during this time I was taking care of my father whose health was deteriorating. Throughout graduate school and while living with my father in rural North Texas, I became isolated and somewhat disconnected from the local community. Because of these social and familial circumstances, I retreated into reclusively, and likely as a result, I found affinity with a Macbook computer and online social networks.

Media were tools that I used to not only document research but they also provided a means of escaping, albeit temporarily, from the grind of graduate school and the solitude of caring for a dying parent. In 2006 I posted my first YouTube video online. There was something about performing in front of a digital camera and then uploading a four-minute video to a social media site (SNS) for strangers to comment on and ridicule that provided me with a sense of community and place. While locked in my room researching one day, my father, who was checking-in on me asked, "What are you writing on your computer?" His question, imbued with both care and wonder, has stayed with me years after his death.

My father was born in 1930; one year after the U.S. stock market crashed that subsequently gave rise to The Great Depression. He never used a computer, and it was only during his late sixties and throughout his seventies that he used a cell phone. He would have never described his relationship with a cell phone through affinity, but rather perceived the mobile artifact as an inconvenient sign of the times. As I reflect back to that moment when he asked me about what I was writing on the computer, I think about his orientation to technology. At the time, I would not have described what I was doing on my computer as writing. However, my father’s way of knowing how a computer functioned was intuitive, and in fact true. I do write on my computer, as in mark, produce, and compose—just not with a led pencil or ink pen.

Thinking too about my father, who was a writer and oil painter, and his relationship to the pen and paintbrush, these were technologies through which he found catharsis, just as the button and mouse are instruments through which I can connect digitally with others and express myself. As a child of the Great Depression, and a nomad of this digital world, my father and I, respectively, used the technologies and media of our generations to write our ways into knowing, participate in culture, and to find a sense of place in the world.

When I first began to work with young people who were involved in foster care and juvenile justice systems, I noticed that they too were finding ways to connect with others using social, digital, and mobile media. They were composing on and connecting to publicly mediated networks, engaging in what Alice Marwick, Ph.D. calls ethnography of display[1]. Some of these young people had lost parents at an early age, transitioned in and out of school, and had difficulty finding work. Despite lacking supportive ties to family, school, and work, these young people still managed to find ways to digitally participate in the circulation of culture and knowledge, even with limited access to computers, cell phones, and the Internet. I spent time working closely with young people who, when given access to borrowed computers and Internet WiFi (wireless technology that enables connection to the Internet) would log on to Facebook or WordPress (a popular blogging web platform), connect with friends and share media artifacts like digital pictures and videos. These young people were not simply consuming media, but also participating—despite their circumstances, in the meaning making processes through relatively public and mediated social networks.

As I approach this research, I am again drawn back in time to the question my seventy-year-old father asked me nearly ten years ago. A question that at its core wants to know: What do we do with media and networked technology, and why do we do it, particularly during episodes in our lives when we seem dislodged from support networks that are meant to ground us? MIT specialist, Sherry Turkle writes in her book Alone Together (2011) that “[t]he network is seductive [and] if we are always on, we may deny ourselves the rewards of solitude” (pg. 3). While it may be true that relentless connection to networked technology can impose new communication challenges for people and our relationships, one might consider how networked technology can mediate information-seeking practices and connection, particularly for those who, during moments of difficult transition, find solitude a nuisance, whose offline supportive ties are scarce commodities, and for those whose privacy is complicated by federal legislation and institutional regulations.

This subtle consideration about our relationship to/with each other and networked technology, along with the question that asks what is it that we do with media guides this research. I am compelled to know more about how young people who are characterized as disconnected and vulnerable might find a sense of community and place, if at all, through media and technology. Furthermore, I think about what these findings might reveal about the organization and space of their social ties and networks. My inquiry here is motivated by care for and wonder about the lives of young people I have had the privilege of working with for nearly two years. This exploratory research is also an ode to my father’s loving question years before. And as Cris Beam writes in her book about youth in foster care, To The End of June (2013), this research is a way for me to look.

[1] On February 20, 2014 during a presentation at Teachers College, Columbia University, Alice Marwick, Assistant professor of Communications and Media at Fordham University described the writing and producing that we do via web media as “ethnography of display”. Marwick noted that during the earlier days of blogging and online journaling, text was the primary mode of displaying information. The current web landscape complicates what it means to write our ways into knowing and being because of visual media like images and video. The term “ethnography of display” encapsulates both how people produce publicly online and how these practices overtime tell a story about self-presentation.