[Bibliography] Towards an Anti-Racist Pedagogy in Ed Tech

Welcome CSA 2015! Feel free to peruse the bibliography for Towards and Anti-Racist Pedagogy in Educational Technology.

Welcome CSA 2015! Feel free to peruse the bibliography for Towards and Anti-Racist Pedagogy in Educational Technology.

Aslop, S. & Bencze, L. (2014). Activism! Toward a more radical science and technology education. In Bencze, L. and Alsop, S. (Eds.), Activist science and technology education (1-20). New York: Springer.

Bowen, G.M. (2014). Trajectories of socioscientific issues in new media: Looking into the future. In Bencze, L. and Alsop, S. (Eds.), Activist science and technology education (269-306). New York: Springer.

Dinerstein, J. (2006). Technology and its discontents: On the verge of the posthuman. American Quarterly, 58(3), 569-595.

Dewey, J. (1964a). Ethical principles underlying education. In Archambault, R.D. (Ed.), John Dewey on education (108-138). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Dewey, J. (1964b). My pedagogic creed. In Archambault, R.D. (Ed.), John Dewey on Education (427-439). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Fouche, R. (2012). From black inventors to one laptop per child: Exploring a racial politics of technology. In Nakamura, L. and Chow-White P.A. (Eds.), Race after the internet (61-83). New York: Routledge.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum.

Fuhrman, S. (2015). Big data in education. Education Update.

Hedberg, J.G. (2011). Towards a disruptive pedagogy: changing classroom practice with technologies and digital content. Educational MEdia International, 48(1), 1-16.

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. New York: Routledge.

Hui Kyong Chun, W. (2012). Race and/as technology or how to do thing to race. In Nakamura, L. and Chow-White P.A. (Eds.), Race after the internet (38-60). New York: Routledge.

Marri, Anand R. (2007). Working with blinders on: A critical race theory content analysis of research on technology and social studies education. Multicultural Education & Technology Journal, 1(3), 144-161.

Milberry, K. (2014). #OccupyTech. In Bencze, L. and Alsop, S. (Eds.), Activist science and technology education (255-268). New York: Springer.

Patton, D.U., Eschmann, R.D., Butler, D.A. (2013). Internet banging: New trends in social media, gang violence, masculinity and hip hop. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(5), 54-59.

Rodriguez, A. (2014). A critical pedagogy for STEM education. In Bencze, L. and Alsop, S. (Eds.), Activist science and technology education (55-66). New York: Springer.

Roth, W.M. (2014). From-within-the-event: A post-constructivist perspective on activism, ethics, and science education. In Bencze, L. and Alsop, S. (Eds.), Activist science and technology education (237-254). New York: Springer.

Sanchez-Casal, S. and Macdonald, A. A. (2002). Feminist reflections on the pedagogical relevance of identity. In Sanchez-Casal, S. and Macdonald, A. A. (Eds.), Twenty-first-century feminist classrooms: Pedagogies of identity and difference (1-28). New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

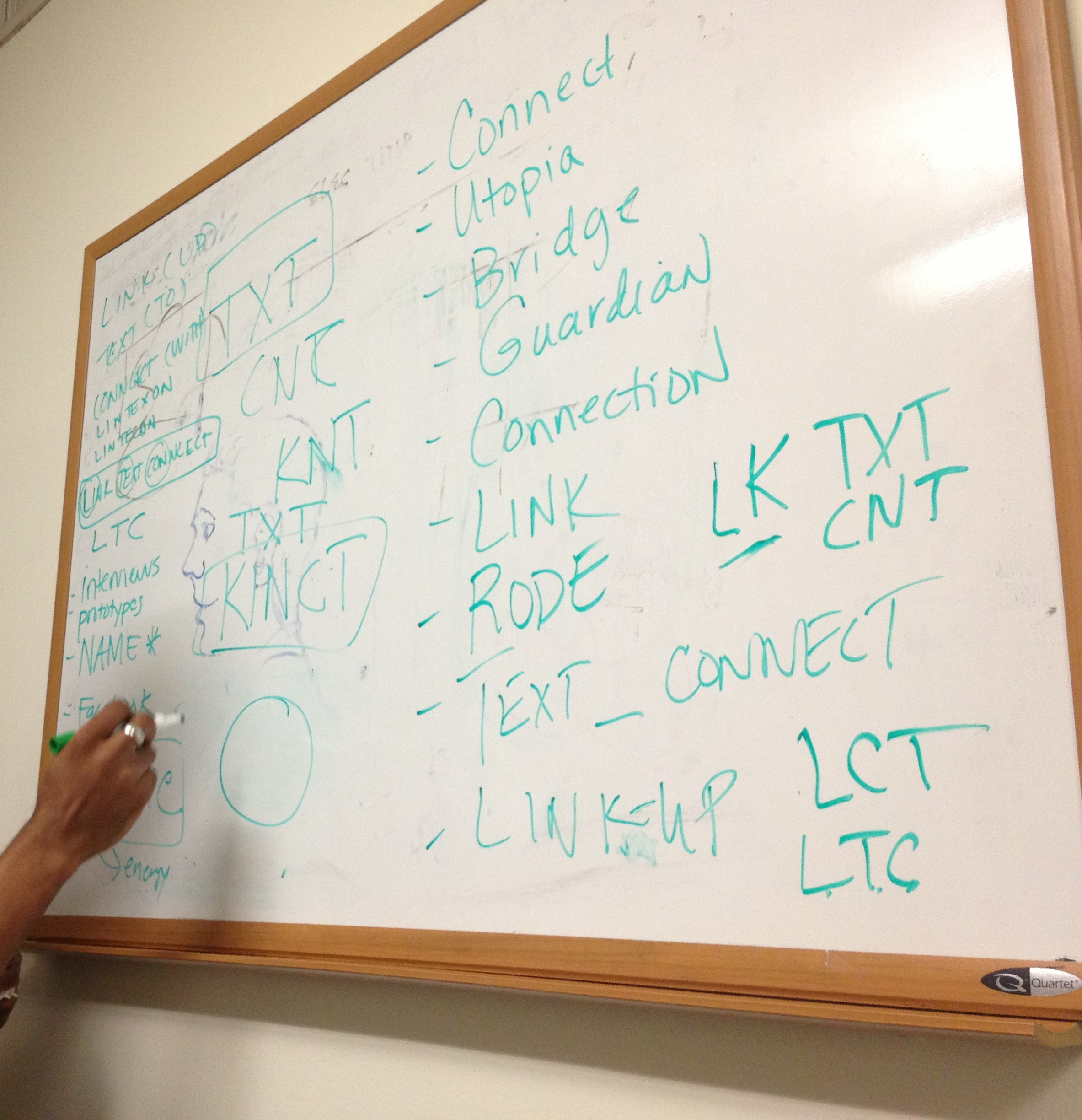

Excerpt from my current research on #PD #mobile #youth #justice

(Photo by Tara L. Conley)

The following is an excerpt from an article draft I'm currently working on about participatory design, mobile text messaging service, and court-involved youth:

During the summer of 2013 amid a controversial mayoral race in New York City[1], mayor Michael Bloomberg vetoed legislation that, in part, would create an independent inspector general to oversee the New York City Police Department (Goodman; 2013) and would allow for an expansive definition of individual identity categories under the current law. The four bills, together named the Community Safety Act (Communities United for Policing Reform; 2012), were brought forth by City Council as a result of a legal policing practice called Stop-and-Frisk. This policing practice allows New York City police officers to stop, question, and frisk citizens under reasonable suspicion of criminal activity.

While New York City residents were at odds over mayoral candidates and policing practices, young people involved in both foster care and juvenile justice systems were developing and designing a free text messaging service that would support court-involved youth in New York City to access resources and services using their cell phones. Three months before Bloomberg vetoed the Community Safety Act in New York City and while the city’s political sexting [2] scandal garnered national attention, several young people and I were discussing ways mobile technology could be used to help court-involved youth stay connected to their communities. Unaware about the extent to which Stop-and-Frisk and other safety concerns affected young people, I brought forth the idea of a text messaging platform that would primarily function as means of connecting court-involved youth to educational resources such as tutoring services and neighborhood jobs. At the time, the purpose of the platform was to create an intimate and anonymous means for young people involved in both foster care and juvenile justice systems to seek out resources beyond the institutions to which they were bound. Cell phones, I thought, would be the easiest and most comfortable way to facilitate a connection between young people and their communities.

However, the more I talked with young people, the more I understood that connecting to their communities not only meant accessing educational resources, job listings, and intervention services like hotlines, it also meant seeing the mobile device itself as a documentation tool and mobile companion for young people as they navigate the terrain of constant surveillance (Ruderman; 2013) and unstable home lives, all while trying to grasp for themselves a sense of belonging amid a psychological battlefield of metropolis dwelling [3].

Notes

[1] While running for mayor of New York City, former US congressman Anthony Weiner was involved in a national sex scandal, of which he admitted to sending sexually explicit text messages to several young women. Weiner’s indiscretions was the focal point of the NYC mayoral race and national news.

[2] Sexting is a term that describes the act of sending and receiving sexually explicit messages usually over a mobile device. The terms “sex” and “texting” began to appear in survey literature as early as 2008. Shortly thereafter the term “sexting” (a word formed by combining “sex” and “texting”) began to appear widely in academic studies and mainstream media and news (see The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy; 2008; Lounsbury, et. al.; 2011, and Ringrose, et. al., 2012).

[3] Simmel (1903) writes about the ancient polis, or city-state, as it relates to the small town. Both the city and town share an anxiety of “incessant threat” by outsiders, or enemies seen as outsiders. Simmel argues that because of this collective anxiety the environment becomes “an atmosphere of tension in which the weaker were held down and the stronger were impelled to the most passionate type of self-protection” (pg. 16). One might argue that the conditions young people experience in the city, particularly in New York City is symptomatic of an anxiety-ridden atmosphere.

References

Communities United for Policing Reform. (2012). About the Community Safety Act. Accessed on Aug. 5, 2013. Retrieved from http://changethenypd.org/about-community-safety-act

Goodman, D.J. (2013). Bloomberg vetoes measures for police monitor and lawsuits. The New York Times. Accessed on Aug. 4, 2013. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/24/nyregion/bloomberg-vetoes-measures-for-police-monitor-and-lawsuits.html?_r=0

Lounsbury, K., Mitchell, K.J., and Finkelhor, D. (2011). The true prevalence of “sexting”. Crimes Against Children Research Center. https://www.unh.edu/ccrc/pdf/Sexting%20Fact%20Sheet%204_29_11.pdf

Ringrose, J., Gill, R., Livingstone, S., Harvey, L. (2012). A qualitative study on children, young people, and ‘sexting’. NSPCC. http://www.nspcc.org.uk/Inform/resourcesforprofessionals/sexualabuse/sexting-research-report_wdf89269.pdf

Ruderman, W. (2013). To stem juvenile robberies, police trail youths before the crime. The New York Times. Accessed on Aug. 4, 2013. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/04/nyregion/to-stem-juvenile-robberies-police-trail-youths-before-the-crime.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

Simmel, G. (1903). “The Metropolis and Mental Life” translated and published in The Sociology of Georg Simmel, ed. Kurt Wolff (Glencoe, IL: Free Press, 1950), 409-424.

The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. (2008). http://www.thenationalcampaign.org/sextech/pdf/sextech_summary.pdf

The Boomerang Effect (and why Jacqueline's story is important)

This post first appeared on The Loop 21 three years ago (The Loop 21 has since deleted the article...boo!). My article prompted a thoughtful response from director, Reginald Hudlin, which was also deleted by The Loop 21 (ugh!). Anyhoo, here's my take on one of my favorite movies of all time, Boomerang, and why I think Jacqueline's story is important.

This post first appeared on The Loop 21 three years ago (The Loop 21 has since deleted the article...boo!). My article prompted a thoughtful response from director, Reginald Hudlin, which was also deleted by The Loop 21 (ugh!). Anyhoo, here's my take on one of my favorite movies of all time, Boomerang, and why I think Jacqueline's story is important.

It’s hard to believe that eighteen years ago audiences around the country first laughed out loud at the box office hit film Boomerang (1992). The movie, arguably one of Eddie Murphy’s best films, introduced us to Bony T (Chris Rock), the incomparable antics of Strange (Grace Jones), and blessed us with Mr. Jackson’s (John Witherspoon) now legendary phrase, “Bang! Bang! Bang!” Without a doubt, Boomerang is one of the best American comedies of the twentieth century.

I’ve watched Boomerang at least several dozen times throughout my life (I was eleven years old when the film was first released). Each time I watch the film, I gather something new, whether it be one of Tyler’s (Martin Lawrence) pro-black conspiracy theories or the unintended comical reactions of an extra on the exercise machine in the background.

However, as I’ve gotten older, I’ve watch the movie with a different lens--a more grown up one, if you will. Needless to say, the more I watch Boomerang the more I notice Robin Givens’ character, Jacqueline, as the quintessential villain presumably because she can manage a career and a sex life.

Let me explain.

I've always been more interested in Jacqueline, a highly successful and sexual Black woman, than Marcus, the predictable dunce who eventually learns a lesson about love. My main argument is that while both Marcus and Jacqueline are flawed, it only seems that Marcus gets rewarded in the end by living a happy life with Angela (Halle Berry) and Jacqueline gets vilified, never seen or heard from again. The thematic conclusion presented in the plot eerily reflects real world assumptions about sex and romantic relationships.

(Note: The point of this article is not to set up useless binaries between heterosexual men and women, but to explore how the relationships presented in Boomerang might be a reflection of society's problem with successful, independent, sexual, and loving women.)

I’ll start with the counter arguments then explain the problems with each as it relates to a larger discussion of gender and sexuality in the context of romantic relationships.

Counterargument #1: It’s not about Jacqueline being able to manage a career and sex life, it’s about my man Marcus being done wrong!

In fact the story is also about Jacqueline, though the Hudlin Brothers and Eddie Murphy chose to highlight Marcus as the central character who can learn from love. We never know what happened to Jacqueline after she told Marcus “it’s over” and left hurriedly to catch the cab. We also don’t know what happened to Jacqueline after Marcus left her in the bed upon realizing he loved Angela. Did Jacqueline find another lover, (perhaps a woman?), to fill the void that Marcus left? As the audience, we’re left to assume that Jacqueline 'got what she deserved' because she was cold-hearted (similar to how Marcus was earlier in the movie).

Interestingly enough (as noted on the DVD audio commentary), “the Executives at Paramount Pictures were nervous about casting Robin Givens in the film because she was disliked by many in the general public due to her past with Mike Tyson.”

Interestingly enough (as noted on the DVD audio commentary), “the Executives at Paramount Pictures were nervous about casting Robin Givens in the film because she was disliked by many in the general public due to her past with Mike Tyson.”

Hudlin continues to say however, “that actually made [Givens] perfect for the role, that she was this formidable person, and a match for Eddie Murphy, who also had an increpid reputation as a ladies' man. So, I wanted the audience to feel like this would be a fair fight.”

Mr. Hudlin’s boxing references were not unintentional. Robin Givens was perfect for the role, not simply because she could act, but because of her public battle with ex-lover, Mike Tyson. Essentially Jacqueline’s character, played by a women who in real life was was ostracized publicly for her relationship with a successful Black man, was thought of as a formidable opponent to Eddie Murphy’s character Marcus because she could match wits with him sexually and intellectually.

Robin Givens was the perfect woman to play Jacqueline, the villain, because in real life she was the villain.

The idea of woman as villain, both real and imagined, also speaks to a larger societal issue concerning successful and outspoken women who publicly battle with (what should be) private romantic relationships. Often times these battles involve more than simply a lovers quarrel, but rather serious issues concerning domestic violence and sexual abuse. Whether it be Mike Tyson or Marcus Graham, to suggest that either have been 'done wrong' by a woman seems a bit shortsighted, but nonetheless a predictable response in a patriarchal society that has yet to accept its role in the proliferation of gender biases while minimizing the complexhood of a woman's sexuality within romantic relationships.

Counterargument #2: Jacqueline is karma in the flesh, not a villain.

Women are not personifications of abstract ideas, but rather, we are human beings; the stuff that personification is actually made of. As Hollywood depicts women as karma in the flesh and thereby saviors of men, the reality is that "the over-reliance on 'woman wisdom' leads to lack of accountability on the part of men." In a society that is infatuated with categories, we have to keep in mind that each time we label women and men based on constructions, we also Otherize them, turning the individual into an idea or an object that’s easier to judge, trivialize, and indeed scrutinize.

By accepting Jacqueline as the villain, we also assume that her purpose is to teach Marcus a lesson, and essentially make us feel better about reconciling the guilt of treating someone in our lives wrongly. What about Jacqueline’s autonomy and personhood? Granted she too was flawed, as noted earlier, but can we honestly accept that her flaws only served as means to make Marcus (the man in her life) a better person?

Notably, the scene between Marcus and Angela highlights this issue. When Marcus audaciously tells Angela, “I’m a better person because of you” we understand that Marcus still doesn’t get it (as illustrated when Angela slaps him in the face). Though despite Marcus’ misuse of Angela, he still gets the girl in the end.

The Importance of Jacqueline’s Story

The Importance of Jacqueline’s Story

Which brings me back to why I’m interested in Jacqueline’s story. Though she’s as flawed as Marcus, she’s also extremely powerful in her own right. Her sexuality, intelligence, and success, though mysterious for the most part, are relatable. It’s unfortunate, however, that her story wasn’t intriguing enough for the writers to make it central to the plot. Though, it may just be a refection of how we haven’t reached the point yet where stories like Jacqueline’s are welcomed in public discourse about romantic relationships. While Steve Harvey tells women and men how to act, some of us are (or will eventually be) brave enough to tell our own stories.

At times, I wish another Boomerang would be produced so I can admire the characters all over again. But as one friend reminded me, "some movies have to be appreciated in our past, never in present."

Indeed.

My NCA Statement on Feminism and Communications

Due to lack of travel funds I am unable to attend NCA (National Communication Association) Conference 2012 this year. Below is my official statement that will be presented on my behalf during Saturday morning’s roundtable session entitled “Critical Perspectives on Feminism and Activism in the Third Wave”. I’ve spent the last few years grappling with feminist identity. Despite over the years having performed so-called “feminist duties” as an academic and as a political activist, (i.e. earning a MA in Women’s Studies, caucusing for Hillary Clinton in 2008, and volunteering as a hotline operator for a women’s shelter), I realize that my feminism has less to do with declaring a feminist identity and more to do with how my feminism emerges through work and scholarship, both of which almost always reflect a feminist ethic grounded in an inquiry stance. That is, I’m always questioning my-self in relation to Other; always replaying Trinh T. Minh-ha’s mystifying question in my head, “If you can’t locate the other, how are you to locate your-self?”

I worry, however, that feminism as a discipline, as a politic, as a form of activism, and as an idea(l) has become institutionalized within a western moral, ethic, and capitalistic framework that looks more and more like hierarchy, chronology, and characterized by waves (eg. generations). I also wonder about feminism as a capital enterprise. The notion of “professional feminism” troubles me. I realize folks have to make a living off of their work, but the label “professional feminist” conjures up awkward emotions. And no, I’m not referring to the welcomed contradictions of personhood that Gloria Anzaldúa brilliantly theorizes in Borderlands La Frontera, but rather I’m talking about the idea of professional feminism that exist in conflict with how I understand feminist consciousness; that is, something as sacred. Something that cannot be bought or sold. Untouched.

That said, however, I’m happy to see and feel feminist ideas spread throughout our home lives, our governments, our schools, and disseminated by way communication technologies.

To see feminist activism travel throughout time and space has been incredible to witness. With technology we are able recognize the multivalent nature of our potential of doing feminism, and by extension being feminist. Feminists have been able to spread our advocacy projects across time and space, and organize our bodies to protests in cities and neighborhoods across the globe. We have brought together domestic and international partners as we strive for justice and relief. We have called out others and at times we have had to confront ourselves. We have moved our advocacy beyond stationary online and offline spaces.

As we move throughout these spaces and places, I hope we can approach third space consciousness where we fight as much for the preservation of our selves as we fight for the preservation of others. This movement toward consciousness—born of techno advocacy practices that span across computer mediated and non-computer mediated contexts, is a threshold space of place where we can (I hope!) see ourselves through the eyes of others and by way of panoramic views.

This kind of feminism spreads like sun rays and warms me up everytime I think about it.

Feminist theory and ethnography is peppered throughout the discipline of communications. I know of researchers at my institution who look towards feminist theory and ethnography to inform their work in communications and education, and of course, I have peers who see no use for feminist theory and ethnography. In fact, they may have never heard of feminist theory and feminist ethnography throughout their academic careers. The beauty of academia and research is that we can take multiple approaches to understanding the worlds around us. As a researcher and scholar of both education and communications, I carry with me an understanding of feminist theories and methodologies that I apply to my research on media, Internet/web 2.0, and youth culture. Feminist theory and ethnography are just a few of my lenses, and I don’t expect anyone else to wear them as I do when approaching research. I do, however, expect that the discipline of communications will continue to embrace interdisciplinary approaches. I expect communication scholars to acknowledge and embrace transdisciplinary analyses informed by theoretical approaches that take into account experiences and storytelling at the intersection of gender, class, sex, sexuality, ‘race’, dis/ability, religion, tribe, and ecology.

"Consciousness of exclusion through naming is acute"

Consciousness of exclusion through naming is acute. Identities seem contradictory, partial, and strategic. With the hard-won recognition of their social and historical constitution, gender, race, and class cannot provide the basis for belief in ‘essential’ unity. There is nothing about being ‘female’ that naturally binds women. There is not even such a state as ‘being’ female, itself a highly complex category constructed in contested sexual scientific discourses and other social practices. Gender, race, or class-consciousness is an achievement forced on us by the terrible historical experience of the contradictory social realities of patriarchy, colonialism, and capitalism.

~ Donna Haraway, "A Cyborg Manifesto"

Photo source