On intellectual hubris and participatory design #PD #research #justice

The following is an excerpt from an article draft I’m currently working on about participatory design, mobile text messaging service, and court-involved youth:

The following is an excerpt from an article draft I’m currently working on about participatory design, mobile text messaging service, and court-involved youth:

Engaging in rigorous research is taxing, and if done right, humbling. The researcher not only concerns herself with conducting ethical practices, but she also has to ensure that the work; the calculating numbers and documenting observations in field notes are properly attended to. When the researcher engages in participatory design work; however, she confronts an additional and uncomfortable layer to research logistics: intellectual hubris. Her weaknesses as researcher and an advocate are almost always revealed during the participatory design process. This revelation of ineptitude can be sobering, especially considering that the researcher spends a good portion of her adult life studying in academia; a space that imparts on scholars and researchers a misleading message that the more we do research, the better we will have an understanding about phenomenon, social organization, and cultural emergence. We come to accept the half-truth that we, indeed, are experts, and take with us into the community an aura of academic arrogance. But in order for the process to flourish, and for all participants to contribute effectively to design, the researcher must suspend an expert reasoning that brought her in to the field in the first place. When the researcher goes into the field and engages in work with community members, not just to study on behalf of them, but also with them, she begins to realize that expertise is at its best when scrutinized, distrusted at first, and continually refined by the community she wishes to serve through design.

Excerpt from my current research on #PD #mobile #youth #justice

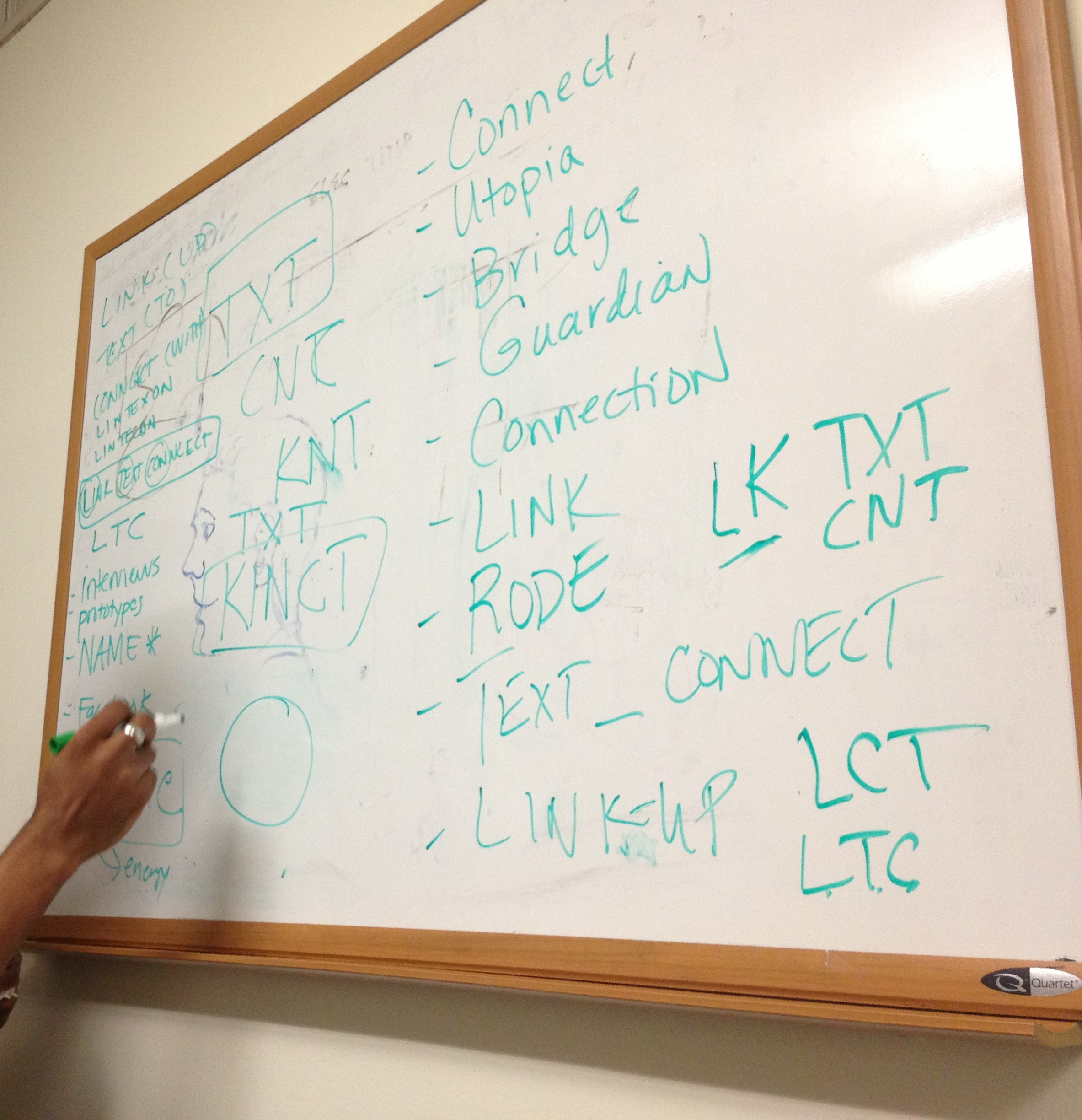

(Photo by Tara L. Conley)

The following is an excerpt from an article draft I'm currently working on about participatory design, mobile text messaging service, and court-involved youth:

During the summer of 2013 amid a controversial mayoral race in New York City[1], mayor Michael Bloomberg vetoed legislation that, in part, would create an independent inspector general to oversee the New York City Police Department (Goodman; 2013) and would allow for an expansive definition of individual identity categories under the current law. The four bills, together named the Community Safety Act (Communities United for Policing Reform; 2012), were brought forth by City Council as a result of a legal policing practice called Stop-and-Frisk. This policing practice allows New York City police officers to stop, question, and frisk citizens under reasonable suspicion of criminal activity.

While New York City residents were at odds over mayoral candidates and policing practices, young people involved in both foster care and juvenile justice systems were developing and designing a free text messaging service that would support court-involved youth in New York City to access resources and services using their cell phones. Three months before Bloomberg vetoed the Community Safety Act in New York City and while the city’s political sexting [2] scandal garnered national attention, several young people and I were discussing ways mobile technology could be used to help court-involved youth stay connected to their communities. Unaware about the extent to which Stop-and-Frisk and other safety concerns affected young people, I brought forth the idea of a text messaging platform that would primarily function as means of connecting court-involved youth to educational resources such as tutoring services and neighborhood jobs. At the time, the purpose of the platform was to create an intimate and anonymous means for young people involved in both foster care and juvenile justice systems to seek out resources beyond the institutions to which they were bound. Cell phones, I thought, would be the easiest and most comfortable way to facilitate a connection between young people and their communities.

However, the more I talked with young people, the more I understood that connecting to their communities not only meant accessing educational resources, job listings, and intervention services like hotlines, it also meant seeing the mobile device itself as a documentation tool and mobile companion for young people as they navigate the terrain of constant surveillance (Ruderman; 2013) and unstable home lives, all while trying to grasp for themselves a sense of belonging amid a psychological battlefield of metropolis dwelling [3].

Notes

[1] While running for mayor of New York City, former US congressman Anthony Weiner was involved in a national sex scandal, of which he admitted to sending sexually explicit text messages to several young women. Weiner’s indiscretions was the focal point of the NYC mayoral race and national news.

[2] Sexting is a term that describes the act of sending and receiving sexually explicit messages usually over a mobile device. The terms “sex” and “texting” began to appear in survey literature as early as 2008. Shortly thereafter the term “sexting” (a word formed by combining “sex” and “texting”) began to appear widely in academic studies and mainstream media and news (see The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy; 2008; Lounsbury, et. al.; 2011, and Ringrose, et. al., 2012).

[3] Simmel (1903) writes about the ancient polis, or city-state, as it relates to the small town. Both the city and town share an anxiety of “incessant threat” by outsiders, or enemies seen as outsiders. Simmel argues that because of this collective anxiety the environment becomes “an atmosphere of tension in which the weaker were held down and the stronger were impelled to the most passionate type of self-protection” (pg. 16). One might argue that the conditions young people experience in the city, particularly in New York City is symptomatic of an anxiety-ridden atmosphere.

References

Communities United for Policing Reform. (2012). About the Community Safety Act. Accessed on Aug. 5, 2013. Retrieved from http://changethenypd.org/about-community-safety-act

Goodman, D.J. (2013). Bloomberg vetoes measures for police monitor and lawsuits. The New York Times. Accessed on Aug. 4, 2013. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/24/nyregion/bloomberg-vetoes-measures-for-police-monitor-and-lawsuits.html?_r=0

Lounsbury, K., Mitchell, K.J., and Finkelhor, D. (2011). The true prevalence of “sexting”. Crimes Against Children Research Center. https://www.unh.edu/ccrc/pdf/Sexting%20Fact%20Sheet%204_29_11.pdf

Ringrose, J., Gill, R., Livingstone, S., Harvey, L. (2012). A qualitative study on children, young people, and ‘sexting’. NSPCC. http://www.nspcc.org.uk/Inform/resourcesforprofessionals/sexualabuse/sexting-research-report_wdf89269.pdf

Ruderman, W. (2013). To stem juvenile robberies, police trail youths before the crime. The New York Times. Accessed on Aug. 4, 2013. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/04/nyregion/to-stem-juvenile-robberies-police-trail-youths-before-the-crime.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

Simmel, G. (1903). “The Metropolis and Mental Life” translated and published in The Sociology of Georg Simmel, ed. Kurt Wolff (Glencoe, IL: Free Press, 1950), 409-424.

The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. (2008). http://www.thenationalcampaign.org/sextech/pdf/sextech_summary.pdf

My Selfie Project on Instagram

The Selfie Project is a social media experiment I started on Instagram in order to communicate out of a need to (be) love(d). The project's mission is inspired by the Abbot, a character in Carl Sagan's novel Contact.

The Selfie Project is a social media experiment I started on Instagram in order to communicate out of a need to (be) love(d). The project's mission is inspired by the Abbot, a character in Carl Sagan's novel Contact.

The Abbot asks, "But why do we communicate? [...] Why do we wish to exchange information?" The Abbot concludes, "I believe that we communicate out of love or compassion."

The selfie (a picture taken of yourself with the intent to upload to social media) has become a cultural phenomenon and social practice that reflects a desire to author ourselves while living and being in an era of complicated and intrusive privacy and surveillance practices, all while the body and self image are perpetually scrutinized.

Does narcissism play a role? Perhaps. But that's not my focus here.

Instead, I understand that through the selfie we seek to reach out to others, confront our mortality through digital reflections, and expose pieces of who we believe we are through the mobile self portrait. The selfie becomes a communicative means through which we articulate identity, emotions, and desire. And yes, the selfie, as practice, can be an exercise of self-deprecation.

With the Selfie Project, I attempt to show that there is more to the selfie than the self. Accompanied by poetry, song lyrics and thoughts, there's you.

This is my love story.

Request to follow me on Instagram @Friday025

#TheSelfieProject

Court-involved youth and social meanings of mobile phones

photo by Tara L. Conley

“The mobile is the glue that holds together various nodes in these social networks: it serves as the predominant personal tool for the coordination of everyday life, for updating oneself on social relations, and for the collective sharing of experiences. It is therefore the mediator of meanings and emotions that may be extremely important in the ongoing formation of young people’s identities” (Stald; 2008, pg. 161).

"Dependency Court involved youth rarely have access to a computer or cell phone, and even when they do, it is often only for a short period of time" (Peterson; 2010, pg. 7).

The following is a conversation about cell phones between me and young people involved in foster care and juvenile justice systems. This excerpt is part of ongoing research. Please do not republish.

Tara: I have a question. You all have cell phones, right? And they’re reliable? Do young people [who are court-involved] have cell phones? Do they have data plans? Do they have Smartphones? Do they have flip phones?

Male 1: Some of them have flip phones. Some of them have Smartphones. There are some of them who are scared to pull out their flip phones because...

Female 1: They may get picked on.

Male 1: Exactly!

Tara: They might what?

Female 1: Picked on.

Tara: Picked on? Really?

Male 1: Yes!

Tara: Because they have a flip phone and not a Smartphone?

Male 1: Yes!

Tara: That’s horrible.

Male 1: Kids are vindictive.

Male 2: If you still got a Blackberry you might get picked on.

Female 1: I have a Blackberry. How does that make me less of a person? Because I don’t have an upgraded phone like you?

Male 1: I like it! My Blackberry. I like it more because it’s more of a useful phone than the iPhone and the Galaxy.

Female 1: But you know what? I also think it’s the media that portrays it that way. Like we need it.

Male 1: Of course.

Female 1: It’s like water. Our tap water gets checked everyday to make sure it’s safe for our bodies, but [bottled water] might not get checked as much, but they make it seem like we need it more.

Male 1: But see, if you want to talk about that, that’s on a whole other level. That’s propaganda!

Female 1: But they make it seem like we need this special water.

Male 1: Yeah! They do that with everything! It’s how the government makes money off of the foolish.

Male 2: But then there’s a lot of girls who be like, ‘Oh, if you don’t have an iPhone 5, you’re not popular.’

[Laughing]

Male 1: Yup.

Male 2: The kids get into stuff like that you know. So, I mean there are some kids who don’t have a phone...

Tara: You have an iPhone?

Male 1: Yeah, the 5.

Tara: You have an iPhone?

Female 2: No, the Galaxy Exhibit.

Tara: But they’re all Smartphones?

Male 1, Male 2, Female 1: Yeah.

Male 1: Most of the time, look, it’s hard as hell right now to find a flip phone.

[Laughing]

Male 1: I’m not even going to lie, if you got a flip phone, I’m probably gonna laugh.

[Laughing]

References

Peterson, S. B. (2010). Dependency court and mentoring: The referral stage. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Stald, G. (2008). Mobile identity: Youth, identity, and mobile communication media. Youth, Identity, and Digital Media. Edited by David Buckingham. The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Media and Learning. pp. 143–164. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Transcribing data on a Sunday afternoon

Excerpt of transcribed audio from the first TXT CONNECT youth advisory board meeting on March 12, 2013:

What we’re doing is building a communication platform for these young people. It’s not just mobile text messaging. It’s Facebook--and another thing I was thinking with the Facebook page is to do exactly what you guys are saying and suggesting, which is to build this community online where young people can feel like ‘Okay, I know exactly where I need to go to get information.’ The platform that we’re trying to build--the purpose of it is to connect all of these resources together for young people. It’s like a one-stop shop for [court-involved youth] who want to get information about A, B, or C. They know they can go to whatever it is that we’re calling it.