To Live and Die in Social Media: What We Can Learn From Amanda Todd and Felicia Garcia

On September 7, 2012, Vancouver teen Amanda Todd posted an 8-minute black and white YouTube video, "My story: Struggling, bullying, suicide, self harm" chronicling her struggles with being teased and harassed by fellow classmates. Todd doesn't speak at all throughout the video, and instead holds up placards in front of a webcam. Each piece of paper outlines her story while viewers are provided with a glimpse into Todd's experiences as a victim of cyberbullying, and as according to Naomi Wolf, a victim of adult male cyberstalking. Others have noted that Todd was also victim of slut shaming, or the idea of "shaming and/or attacking a woman or a girl for being sexual, having one or more sexual partners, acknowledging sexual feelings, and/or acting on sexual feelings" (Finally Feminism).

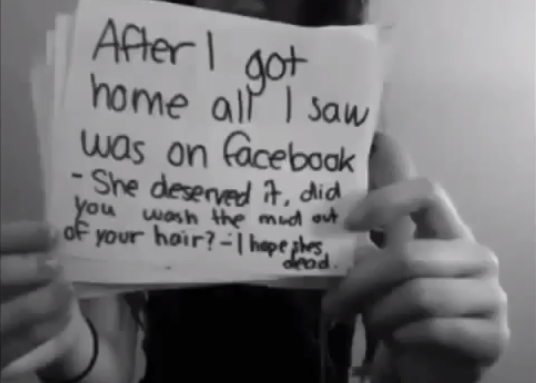

When describing an altercation she had with her classmates at school, Todd writes, "After I got home all I saw was on Facebook - 'She deserved it. Did you wash the mud out of your hair? - I hope she's dead.'"

On October 10, 2012, approximately one month after Todd posted the video on YouTube, she was found dead after an apparent suicide attempt.

On October 24, nearly two weeks after Amanda Todd reportedly committed suicide, Felicia Garcia, a Staten Island teenager jumped in front of a moving train in New York City. Friends and family said Garcia was bullied in school and online because rumors were spreading that she'd been sexually active with football players at her high school. The last words a friend heard Garcia speak right before falling backwards in the path of a moving train were, "Finally, it's here."

Though Garcia's classmates didn't seem to think she was in trouble, a quick glance at Garcia's Instagram pictures tells another story.

Similarly to Todd posting on YouTube, Garcia posted, what I believe to be her last cry for help via Twitter twelve days before she decided to take her own life.

It's heartbreaking to watch our young people take their lives as a result of being bullied by other teens and adults online. As a researcher, I wonder why our young people, girls and boys, decide to use social media as one of the last forms of communication before killing themselves. While it seems like a classic case of cry-for-help, social media further complicates this psychoanalytic narrative by the so-called spectacle in the form of retweets, @ replies, favorites, and likes.

I have to wonder what Amanda and Felicia felt while uploading and posting. What did they really wish to communicate? And has social media now become an alternative to the handwritten suicide letter?

I recently spoke with The Media Bytes about young people in the digital age. I mentioned Amanda Todd in our conversation, in that I believe we failed this young girl in many ways. We had access to knowing and seeing her struggles in a mediated and visible space, yet still we were unable to, or not willing to intervene. During the interview I mentioned that perhaps seeking out social and public spaces while struggling essentially comes down to our basic human need to connect with someone; anyone who will watch our videos and read our tweets.

I understand this need to connect all too well as I also struggled, and was diagnosed with severe depression and post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after my father passed away in 2008. I took to singing on Youtube early on while my father was sick. It was a cathartic response to coping with death and dying. It still is. I'm sure if I revisit my Twitter streams, Facebook updates, blog posts, and even SMS text messages during that time immediately after my father's death, I would see myself in my most rawest and vulnerable form. There was something about singing and talking to a camera, then uploading to a public site that allowed me to let go. To where and to whom I let go in this public space was, and is always a risk. But for Amanda and Felicia it was more than simply letting go publicly online, it was a permanent disconnection from a space so-called the 'real' offline world.

Now we are left with YouTube videos, tweets, and Instagram photos that will continue to remind us of our failure as a tribe in the global village.

That said, however, ubiquitous use and mainstream presence of social and mobile media provide a unique opportunity for adults (and anyone else who cares about the well being of young people) to better address youth in crisis. I recognize that the idea of 'crisis' itself carries with it a ton of baggage; what exactly is meant by crisis? Is crisis a word we only use for certain 'kinds' of communities? Is the very idea of wanting to un-do crisis problematic because it automatically assumes something needs to be fixed? And might that 'something' be the child? One look at the comment's section of this post, and the constant victim blaming that ensues, reminds me that we, as a collective, still haven't fully grasped what it means to be empathetic in a crisis situation. So, I recognize the conundrums.

But I also recognize that something unlike anything I've ever witnessed before is happening with our young people in this digital moment. We live in a hypermediated and interconnected world, so much so that we now craft our identities in these public and mediated spaces like corporations do; as brands. We've always created elaborate narratives of ourselves, but now it seems as though these narratives are beginning to take on a posthumous life of their own.

It's fascinating when you think about the posthumous digital life. Yet, I still wonder where do we stand in the midst of this crisis as our young people both live and die in social media?

We simply can't be satisfied with mourning the deaths of these young girls after the fact and behind our computer screens. What keeps us from nurturing our young people while they are alive? What keeps us from engaging them as they explore their multiple and contradictory identities? What keeps us from being more attentive as they express themsevles in these public places---not as a way to police or to monitor inappropriate behaviors---but as a way to gain insight into what's actually happening in their media-rich, public, and interconnected worlds?

Part of what I wish to do as an academic and social entrepreneur is to create spaces where young people like Amanda Todd and Felicia Garcia (who was in foster care) can go to retreat, reconnect, and rebuild. And I believe media and technology can play a transformative role in mediating what I'm calling nurture-networks. But we have to be deliberate and thoughtful in how we further encourage media and technology in the lives of young people, particularly those in crisis.

I recently applied for the Media Ideation Fellowship and my idea is to specifically address the needs and concerns of young people in crisis, namely court-involved youth who are tethered to multiple social institutions like foster care, juvenile, and welfare systems. I'm hoping to create a localized SMS Texline co-developed by and serving the needs of court-inolved youth in New York City. While I understand that media and technology is not *the* answer to address ongoing and dynamic problems young people face in today's world, I do believe that media and tech tools can help to support deliberate efforts in (re)building what's seemingly been broken. As evident with Amanda Todd and Felecia Garcia, our young people are living and dying in these social and mediated spaces, isn't it about time we meet them where they already are?

**Update***

I just discovered that Amanda Todd sang too.