The Need to Educate the Rich Kids of Instagram

From My MEDIAted Life

There is a new Tumblr page that has been getting quite a bit of attention in the last few weeks. It's got an unoriginal, yet strangely catchy title that would cause almost anyone to click on the link: Rich Kids of Instagram. Your finger might hover over the mousepad for a moment--sure that it could not possibly be what the straight-forward label is seeming to describe, yet weary that it most likely is--you wonder if this is what you should be doing with your time? Should you throw a load of laundry in before you make this time commitment for something you might later regret, or worse, that you might absolutely love (but not be able to tell anybody about)? But like so many other viral videos and Internet memes, in which a mere click stands between you andknowing what everyone else is talking about, this site wins over any rational thought, and just like that you feel the pad of your index finger make contact with the cool sensory surface beneath it.

As soon as the URL loads and the site opens, you dive face-first into a scrolling cluster of photographs and hashtags. The images have all presumably been taken by smartphones (most likely iPhones) and have been enhanced through an application called Instagram, which adds different filters to digital pictures and allows them to be uploaded to various social networking platforms (i.e., Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, etc.) instantly and seamlessly. The subtitle of the site is "They have more than you and this is what they do," and the hashtag is #rkoi. The images are first uploaded by the young people who snapped the shots to the RKOI's Twitter account and are then fed onto the Tumblr page for easy viewing.

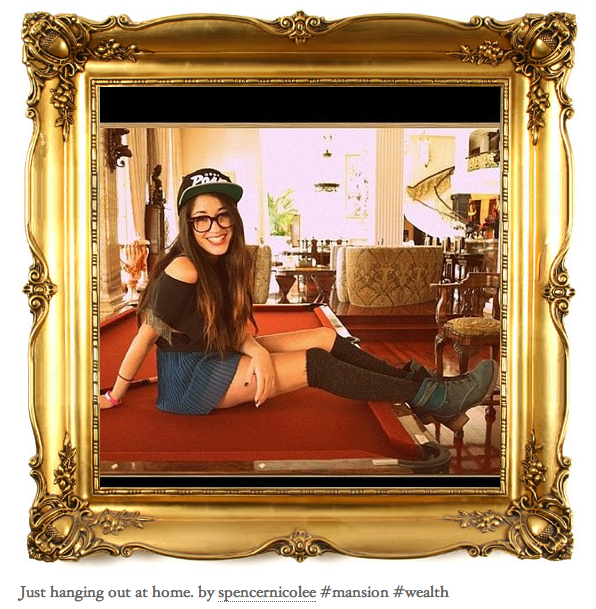

The pictures are displayed in gold frames, suggesting that they are pieces of fine art and conveying an obvious and assumed air of wealth, high culture, and importance. Below each image we find numerous hashtags that the artists have used to 'describe' their masterpieces: #mansion, #wealth, #yacht, #personalchef, #cartier, #NBD (no big deal). The seemingly endless collection of photographs are obnoxious, yet every time I visit the site I find myself clicking from page to page, thirsty for more, even if I've seen the same images four or fives times at this point. What is going on?!As hard as I try to maintain that I am fascinated by this warped website solely for critically analytical and research-related purposes (I'm making a very serious face while saying this), the reality is that I have been 'trained'--socialized and normalized--for decades now to associate the types of images and messages depicted on this site with notions of what "happiness", "success", "popularity", etc. look like; what they mean. If I am having these reactions as a 28-year-old, we must seriously consider how teens might be viewing this site and think about the kinds of conversations that we as educators, adults, parents, can have with the young adults in our lives.

1. The subtle effects and implications of the gold-frame template:

While viewers might feel as if they've become numb to composition after streaming through dozens of images, there is an undeniable novelty and uniqueness in seeing photographs, not oil paintings, housed in these garish golden frames. Instead of invoking a simulated feeling that we are strolling through the quiet rooms of art gallery or museum--observing these masterpieces interspersed on stark white walls--the juxtaposition of the bold, saturated, filtered photographs with the chunky golden frames instead creates a feeling of voyeurism among viewers. We are outsiders being granted access to certain snapshots, postage-stamp views, of what life in the 1% is like.

What might this voyeurism mean for both the creators and consumers of these images? There is an extreme sense of excitement on both ends: for the creators of these media images and messages--they are sharing their lived experiences and material possessions with their peers (and now with wider audiences). Hell, at 14-, 17-, even at 25-years-old (especially in the age of social media and social networking sites), there is a certain undeniable, almost unavoidable [I said almost] narcissism that runs rampant in users' status updates, photos, etc. It's the nature of the beast, but it doesn't make it ok, or mean that we simply and passively accept that this is just how people can and should act as a result. We still must consider, now more than ever, what effects these displays of wealth, materialism, lifestyle and activities might have on the "99%" who have been socialized to perhaps think this representation is 'covetable', on the "1%" who think this representation is "normal." And what it really comes down to is that we should really be taking into account the possible effects that these representations are having on100% of today's youth. Virtually almost (again, almost) every young person in the US is exposed to and interacts with some sort of media on a daily basis--using a cell phone, playing a video game, surfing the Web, or watching television. Today's youth are growing up in an increasingly media-saturated culture and we have a responsibility to help them learn how to successfully navigate their lives through the unprecedented products, behaviors, and activities now being "the norm" in the 21st century.

2. Understanding digital footprints & increasing awareness about digital citizenship:

On August 10, 2012, an article was published on the Bloomberg Businessweek website entitled, "The Very Real Perils of Rich Kids on Social Networks". The article provides an account of how some recent online activities of Alexa and Zachary Dell, daughter and son of Michael Dell (of Dell computers), got them their 15 minutes of Internet fame as well as a terminated Twitter account after Alexa posted a photo of her brother in their private jet, heading to Fiji on RKOI. It was later discovered that this was just one of numerous photographs and statuses containing personal information about her family's whereabouts and activities that she'd posted over the last few months. Mr. Dell pays almost $3 million a year for security protection of his family, so needless to say, this breach of security from an insider was probably both alarming and upsetting. This article provides a powerful illustration and example not only of how quickly information spreads via new media platforms like Twitter and Facebook, but more importantly how easily this information can directly challenge others' efforts of enforcing tangible security measures. In addition, and most importantly, this article serves as an excellent example of the lack of awareness and/or regard that young people tend to have for the often permanent digital footprints that they create as a result of their online activities, particularly on social networking sites. And while some may argue that there are greater implications when the rich (and not necessarily famous) upload pictures of everything from party invitations with the date, time, and location to license plate numbers (all of which can easily and automatically be geo-tagged) to the Twittersphere, the reality is that this online behavior/activity of constantly over-sharing details about their lives can have very real consequences, regardless of one's social class. In a recent New York Times article on the recent upsurge of 20-somethings sharing TMI (too much information) in the workplace, Peggy Klaus, an author and executive coach of corporate training programs explains,

Social media have made it the norm to tell everybody everything...MANY people blame narcissistic baby-boomer parents for raising children with an overblown sense of worth, who believe that everything they say or think should be shared. When I told a British colleague that many Americans were starting to realize that they reveal way too much about themselves, he gave a full-throated laugh and said, “Finally!”

While our first instinct may be to want to protect youth, the takeaway here is not that we need to shield young people from the media tools and content that might cause them to engage in risky activities and behaviors. Instead, we should regard the situation with the Dell children and the realities of the millennial generation outlined by Klaus as important illustrative examples of the fast-forward-moving trajectory that our society and culture is travelling on. As educators, parents, and adults in the 21st century, we have an opportunity and obligation to use these examples to engage the youth in our lives in conversations about digital citizenship, which can include topics of online safety and privacy, cyberbullying, and copyright fair use of online information; media literacy, understanding how and why media messages are constructed and how they can influence beliefs and behaviors; and digital literacy, how to read and evaluate information online.

Use the images on RKOI to ask youth about who they think the image is intended for, what attracts their attention, what lifestyles and behaviors are represented, how different people might interpret the images and messages differently, and what they think may have been left out of the image and why? A conversation about the composition of both the photographs and the website itself—having students think critically about representation, communication, and production—could be integrated into an English lesson on writing about and showing one’s lived experiences through words and images; a social studies lesson on the powerful images and messages from the Civil Rights Movement, juxtaposing them with the very different content displayed on RKOI (in which case, it would also be crucial and a unique way to address issues of race, gender, and class as they relate to both sets of images and messages); or a computers and technology lesson focusing on the dos and don’ts of web-design.

The bottom line is that we must have conversations, many multi-layered conversations, with each other and with youth about sites like RKOI: about the activities and lifestyles represented, as well as the online and offline behaviors fueling the creation of and participation in such sites. It is ok and very normal to want to protect our youth from the unknown, but we’re doing ourselves and them a disservice if we think that leaving these unprecedented realities unaddressed is better than sinking our teeth into them in order to proactively figure all of this out, and we need to do it together--parents and children, teachers and students, peers to peers, or else we're never going to get anywhere.

Emily Bailin is a doctoral student at Teachers College, Columbia University. She's also an an educator, consultant, and public speaker motivated by a passion and determination to collaborate, create, and sustain culturally relevant and socially just pedagogy with other educators to better serve increasingly diverse 21st century learners. You can follow her on Twitter at @emilybailin