Story Melodies Vol. 1: Coming of Age in the City

Story Melodies Vol. 1: Coming of Age in the City from Media Make Change on Vimeo.

Story Melodies Vol. 1 is the first of a series of upcoming digital shorts. Coming of Age in the City highlights the stories of three individuals living in New York City. Their stories are weaved together by the sounds of some of the world's most talented street and subway musicians.

I came up with the idea to begin a series of stories that read like the music we hear. I set out to explore and capture the paradox of sound and image, both of which asks us to consider, what does the image sound like and what does sound look like? Through the paradox we can find meaning.

Because of this project, I've been able to explore nearly every facet of my imagination. I've engaged with my favorite art forms, video and photography, and Ive discovered brilliant sounds of music along the way. After months of collecting sounds and images, I hope to have created a visual and audio work in concert.

I am sincerely thankful to all of the street and subway musicians I listened to along the way. A few listed below:

The Crowd (http://wearethecrowd.com)

Alex Lo Dico Ensemble (http://alexlodico.com)

Charlie Guitar (http://nyccharlie.com/)

Made Over (Youtube: bryken89)

The Meetles (http://meetles.com/)

If anything, through this project I learned that stories are the melody in the key of life. (Hat tip to Stevie Wonder ;-)

Enjoy.

Social Implications of Technology in Education

Despite being a bit outdated, I found Castells' article The social implications of Information and Communication Technologies relevant to what's currently happening with technology and education. Castells breaks down the implications of information and communication technology on society based on several categories:

- Education

- Economy

- Society (inequalities)

- Space/Time (history and urbanization)

I'll limit my discussion to Castells points on education since it's necessary to think about technology in terms of how it impacts current trends in education, particularly urban education. Castells point of view is that ICT tools should be knowledge production tools that supplement, not necessarily replace, other learning tools in education. I appreciate Castells consistent points about generating relevant knowledge through ICT tools. Castells writes,

Our economy is informational because the capacity to generate relevant knowledge, and process information efficiently, is the main source of productivity and competitiveness for firms, regions and countries (237).

Interestingly enough, Castells' point about a productive economy reminds me of Mayor Bloomberg's recent comments about his choice for Chancellor of NYC public schools, Cathie Black. He says of Black,

"There is no one who knows more about the skills our children will need to succeed in the 21st century economy,"

On one hand, I can understand why it's necessary to consider how technology, for instance, can prepare learners for a productive and competitive economy, even if it does come across as Orwellian. Though I wonder what a complete focus on technology's role within education as tool to increase productively and competitiveness in our economy, says about our view of technology and education in general. I come back to Castells main point that technology should be seen as a supplementary tool in schools, and that "increasing computer equipment is not the answer" (236). Technological determinism aside, I think the quantity argument is an important point for us to consider because it speaks to how we use ICT tools as opposed to how many or what type of "latest" tech tools we use.

On another note, I wonder if Black, being a former high profile publishing executive, has any plans for implementing more technology into public schools seeing as how she and Bloomberg seemingly want to prepare our children for a competitive economy - like the little worker bees.

*cough cough*

Final Project (MSTU 4020; Week 11)

Over the past few weeks, I've mulled over ideas for the final project. I think I have a solid idea of what I'd like to focus on. I'm thinking about a literature review that discusses emerging methods of researching identity and communities within digitally connective spaces. I'm particularly interested in Christine Hine's idea of 'connective ethnography'. I think perhaps it's useful to think about how we, as researchers and educators, go about researching and understanding identity and community engagement within this space. I've felt as though some of the methods that have been presented in class, for example, the research studies on Facebook, are missing something - not sure what though. However, I do believe that ethnography can be a great entry point to begin exploring new ways of researching the Internet.

My interest in this topic is grounded by the following quotes (though not limited to these):

"We do not have the empirical ground on which to assess how (if any) online community affects offline community (Bayum, pg. 1998). Bayum asks us to develop an 'emergent model of online community (pg. 1998).

"[When] enacting space, a way of being as you interact with space, a new kind of imaginative space emerges" (Vasudaven, in class, 10/21/10).

"A really good ethnography is one in which you can present it to the community and they're not surprised [by the research]" (Vasudaven, in class, 10/21/10).

Likewise, I may look at how ideas/theories of time and space can lead us toward a new understanding of research models.

A few references I intend to use:

- Gloria Anzaldua's writings on nepantla theory: I will refer to my MA thesis on nepantla theory to see if I can apply this idea, in terms of borderland/liminal space, to understanding what the Internet looks like as "a kind of imaginative space" that emerges.

- Leander & Mckim's Tracing the Everyday 'Sitings' of Adolescents on the Internet: a strategic adaptation of ethnography across online and offline spaces: This article takes a look at ethonography within online and offline social spaces.

- Jankowski's Creating Community with Media: History, Theories, and Scientific Investigations: I'm hoping to use some of the questions that Jankowski and Bayum propose in the article to ground my research paper.

- Christine Hine's Virtual Ethnography & Connective Ethnography and the Exploration of e-Science: Hine's provides useful ideas about connective ethnography that I'd like to explore further.

I'll be looking over more readings from the beginning of the semester this week to see if there's some more useful ideas to work with.

When Qualitative Study Goes Wrong (MSTU 4020; Week 10)

Maybe the title's a bit hyperbolic and maybe I'm a bit frustrated with some of the readings this week because my brain is fried and it's 1:00 am.

Nonetheless, I found The Benefits of Facebook "Friends" profoundly cumbersome. I will concede to the fact that my view of any scholarship on Facebook at this point is nauseating. I feel like we're all staring at a chimpanzee at the zoo as if to study it from a distance only to realize the chimpanzee is really our own silly reflection in the glass window. We're hell bent on finding something "new" or interesting about something that's not really that new or interesting anymore -- at least that's what it seems like. The initial response to Facebook was certainly warranted. Mark Zuckerberg's a genius. Social networking is sexy. And algorithms are the new black. I get that we're entirely obsessed with wanting to understand more about ourselves and our communities. The Internet is a fantastic means of seeing and studying those ideas. But what are we truly getting out of it all?

I have a hard time wrapping my brain around how qualitative studies like The Benefits of Facebook "Friends" have managed to quantify bridging, bonding, and maintaining relationships to the Cronbach’s alpha statistic. This is utterly mind boggling. As I tried to skim the article for definitions of what the authors mean by bridging, bonding, and maintaining relationships, all I found were references to other authors' scales, followed by some random (okay, not random) equation. *pulls out hair* Do we really need statistical data to represent an understanding of how people feel and interact on Facebook? Granted, maybe we do, but boy-oh-boy western society sure does pride itself on rationale and objectivity through scientific measure, even to the point that something qualitative must be quantified.

The fact that nearly all Facebook users include their high school name in their profile (96%) suggests that maintaining connections to former high school classmates is a strong motivation for using Facebook.

Um, okay. Fascinating stuff. So what about those who don't include their high school names, are they less likely to want to maintain connections to former high school classmates? What if the motivation to not include their high school name has absolutely nothing to do with maintaining connections with former classmates? What if that 4% still wants to (and do!) maintain connections, but inserts "High School of the Gifted Pocket Protector Posse" in their profile? What's truly in a name?

This excerpt is really only a small (and silly on my part) example of how quantitative data seems, to me anyway, pointless in the realm of study that's overwhelmingly qualitative.

We've already discussed how complex identity (and identifying) works within digitally connective social spaces. Some of these findings, for instance, do not speak to those complexities or nuances of identity representation and formulation whatsoever.

This particular reading, along with some of the others, brings me back to an issue that I've been thinking about throughout this semester. That is, how do we go about researching digitally connective social spaces? What do we, as researchers and educators, need to consider as it concerns emerging ethnographies in the field? I'm nearly convinced that some of the ways in which we've been going about these "studies" are wrong. And I'm not sure what the alternative is at this point. But it does seem as though we're applying odd and useless methods to a complex area of study.

What of these so-called "findings" is necessary (found on p. 1147)?

- Hypothesis 3a (supported): The relationship between intensity of Facebook use and bridging social capital will vary depending on the degree of a person’s self esteem.

- Hypothesis 3b (supported): The relationship between intensity of Facebook use and bridging social capital will vary depending on the degree of a person’s satisfaction with life.

Talk about mixed ideas; self esteem, social capital (what an abstract notion!), bridging. Is this a psychology study or a study I'd find in a business journal? Even the languaging is wretched.

Aside from the study itself, I worry that the lure of researching SNS outweighs it's effectiveness for educators and scholars. It only seems that these sort of studies are useful stats to inform media soundbites or marketing/PR talking points, but what value do they have toward our understanding of phenomena in communication, societal shifts, technological usefulness, and education (beyond what we already know about physicality, virtuality, embodiness, etc.)? Maybe I'm bothered that the studies aren't moving as fast as the technology itself. Or maybe it's that the studies aren't broad enough in scope (what about Twitter?). Or maybe it's the lateness of the hour and the moment of intellectual exhaustion. Whatever the case maybe, I recognize something unsettling in my gut about all of this sort of research. I really want us to go somewhere with it, to see something truly remarkable about who we are as people and as communities. I want this area of study to inform what else is out there beyond our localities and our realm of awareness. But I just can't see anything biting beyond the proverbial glass window.

On another note, thank God for SuperNews.

Can Our Imaginations Survive in the Age of Digital Connectivity? (MSTU 4020; Week 9)

That's why I don't have a phone. I don't have a Blackberry. I'm not connected like that because I'd rather be thinking. - Dr. David Helfand, Chair of the Department of Astronomy at Columbia University & president of Quest University in Canada.

Last night, I attended the Veritas Forum at Columbia. The topic of discussion focused on truth beyond science featuring scientist Dr. David Helfand (atheist) and Dr. Kenneth Miller (theist). I stayed after the panel discussion to listen in with others ask Dr. Helfand questions about truth, science, God, the universe, and all that jazz. Somehow the mini-discussion turned into a philosophical debate about the brain, perception, and thinking patterns. Amidst the lively chat, Dr. Helfand mentioned that he doesn't own a cell phone mainly because he'd rather be thinking. For Dr. Helfand, the idea of being constantly connected to a digital device intrudes upon how he prefers to think contemplatively and reflectively on a daily basis.

The New York Times article Attached To Technology and Paying the Price reminds me of Dr. Helfand's remarks last night, and it also reminds me of my own meta-relationship with digital connectivity. I eat, sleep, and breath this stuff. Though just as I study it, play with it, and communicate with it, I find myself wanted to get away from it more and more. How is this possible? As I work my way through a doctoral program that emphasizes the use of technology in educational environments, I struggle with exactly where I stand on the technological determinism spectrum. Though, so far through this process, I've become more comfortable in my intellectual skin to assert that it's our use of the imagination, rather than the use of technology itself, that is the most revolutionary act.

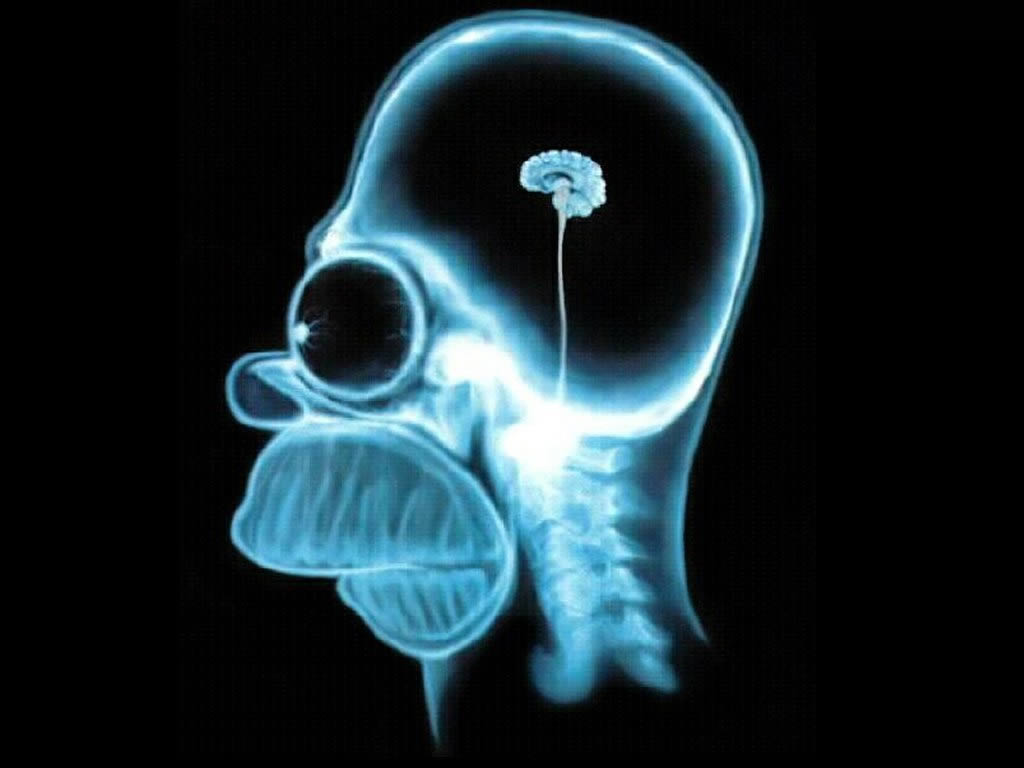

Just as the NY Times article alludes to, our brain make-up is changing. Our multi-tasking behaviors within the digital age affect how we think, how we remember, and how we act. Another scholar, Sven Birkerts, wrote also about Reading in a Digital Age last spring in relation to how our brain reads and imagines text.

This idea of brain re-wiring is an interesting one because it asks us to consider what's to be said for the vast amounts of information we consume through digital connnectivity. Steven Yantis, a professor of brain sciences at Johns Hopkins University, seems a bit less worried about this sort of rewiring: “The bottom line is, the brain is wired to adapt . . . There’s no question that rewiring goes on all the time.” Is this type of shift in brain wiring any different than, say for instance, when written language was introduced to civilization for the first time? Surely, brains were rewired as oral culture was introduced to the written word.

As we consume all of this information, what is the affect on the transference of knowledge? Without having performed any studies, I can only guess that all learners aren't necessarily applying or transferring the information they acquire into knowledge that can be represented and produced. It's one thing to perform a Google search, but it's an entirely different notion to synthesize the information acquired through Google searches into something critical that can ultimately produce knowledge.

I'm reminded of what professor John Black said in my Cognition and Computers class this semester:

The imagination is necessary for transference.

Makes sense.

So, as more media we consume and the more digitally connective we become, what happens to our imaginations, to our thinking processes of reflection and contemplation? Can our imaginations survive in the digital age?