Can Our Imaginations Survive in the Age of Digital Connectivity? (MSTU 4020; Week 9)

That's why I don't have a phone. I don't have a Blackberry. I'm not connected like that because I'd rather be thinking. - Dr. David Helfand, Chair of the Department of Astronomy at Columbia University & president of Quest University in Canada.

Last night, I attended the Veritas Forum at Columbia. The topic of discussion focused on truth beyond science featuring scientist Dr. David Helfand (atheist) and Dr. Kenneth Miller (theist). I stayed after the panel discussion to listen in with others ask Dr. Helfand questions about truth, science, God, the universe, and all that jazz. Somehow the mini-discussion turned into a philosophical debate about the brain, perception, and thinking patterns. Amidst the lively chat, Dr. Helfand mentioned that he doesn't own a cell phone mainly because he'd rather be thinking. For Dr. Helfand, the idea of being constantly connected to a digital device intrudes upon how he prefers to think contemplatively and reflectively on a daily basis.

The New York Times article Attached To Technology and Paying the Price reminds me of Dr. Helfand's remarks last night, and it also reminds me of my own meta-relationship with digital connectivity. I eat, sleep, and breath this stuff. Though just as I study it, play with it, and communicate with it, I find myself wanted to get away from it more and more. How is this possible? As I work my way through a doctoral program that emphasizes the use of technology in educational environments, I struggle with exactly where I stand on the technological determinism spectrum. Though, so far through this process, I've become more comfortable in my intellectual skin to assert that it's our use of the imagination, rather than the use of technology itself, that is the most revolutionary act.

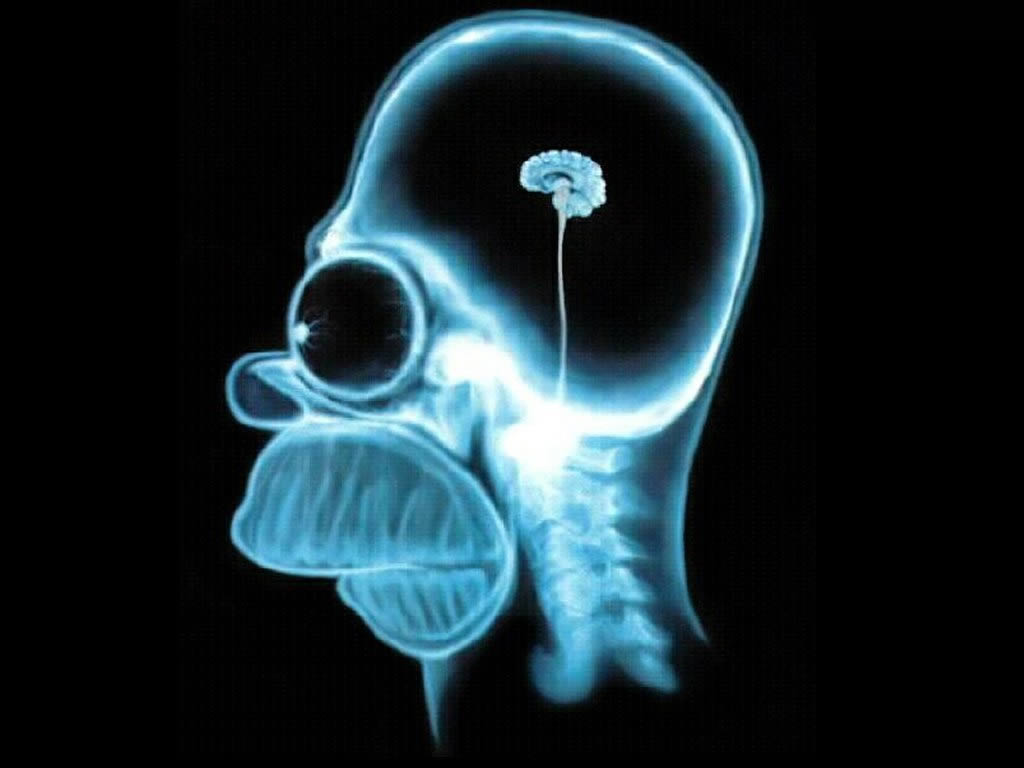

Just as the NY Times article alludes to, our brain make-up is changing. Our multi-tasking behaviors within the digital age affect how we think, how we remember, and how we act. Another scholar, Sven Birkerts, wrote also about Reading in a Digital Age last spring in relation to how our brain reads and imagines text.

This idea of brain re-wiring is an interesting one because it asks us to consider what's to be said for the vast amounts of information we consume through digital connnectivity. Steven Yantis, a professor of brain sciences at Johns Hopkins University, seems a bit less worried about this sort of rewiring: “The bottom line is, the brain is wired to adapt . . . There’s no question that rewiring goes on all the time.” Is this type of shift in brain wiring any different than, say for instance, when written language was introduced to civilization for the first time? Surely, brains were rewired as oral culture was introduced to the written word.

As we consume all of this information, what is the affect on the transference of knowledge? Without having performed any studies, I can only guess that all learners aren't necessarily applying or transferring the information they acquire into knowledge that can be represented and produced. It's one thing to perform a Google search, but it's an entirely different notion to synthesize the information acquired through Google searches into something critical that can ultimately produce knowledge.

I'm reminded of what professor John Black said in my Cognition and Computers class this semester:

The imagination is necessary for transference.

Makes sense.

So, as more media we consume and the more digitally connective we become, what happens to our imaginations, to our thinking processes of reflection and contemplation? Can our imaginations survive in the digital age?