Can Our Imaginations Survive in the Age of Digital Connectivity? (MSTU 4020; Week 9)

That's why I don't have a phone. I don't have a Blackberry. I'm not connected like that because I'd rather be thinking. - Dr. David Helfand, Chair of the Department of Astronomy at Columbia University & president of Quest University in Canada.

Last night, I attended the Veritas Forum at Columbia. The topic of discussion focused on truth beyond science featuring scientist Dr. David Helfand (atheist) and Dr. Kenneth Miller (theist). I stayed after the panel discussion to listen in with others ask Dr. Helfand questions about truth, science, God, the universe, and all that jazz. Somehow the mini-discussion turned into a philosophical debate about the brain, perception, and thinking patterns. Amidst the lively chat, Dr. Helfand mentioned that he doesn't own a cell phone mainly because he'd rather be thinking. For Dr. Helfand, the idea of being constantly connected to a digital device intrudes upon how he prefers to think contemplatively and reflectively on a daily basis.

The New York Times article Attached To Technology and Paying the Price reminds me of Dr. Helfand's remarks last night, and it also reminds me of my own meta-relationship with digital connectivity. I eat, sleep, and breath this stuff. Though just as I study it, play with it, and communicate with it, I find myself wanted to get away from it more and more. How is this possible? As I work my way through a doctoral program that emphasizes the use of technology in educational environments, I struggle with exactly where I stand on the technological determinism spectrum. Though, so far through this process, I've become more comfortable in my intellectual skin to assert that it's our use of the imagination, rather than the use of technology itself, that is the most revolutionary act.

Just as the NY Times article alludes to, our brain make-up is changing. Our multi-tasking behaviors within the digital age affect how we think, how we remember, and how we act. Another scholar, Sven Birkerts, wrote also about Reading in a Digital Age last spring in relation to how our brain reads and imagines text.

This idea of brain re-wiring is an interesting one because it asks us to consider what's to be said for the vast amounts of information we consume through digital connnectivity. Steven Yantis, a professor of brain sciences at Johns Hopkins University, seems a bit less worried about this sort of rewiring: “The bottom line is, the brain is wired to adapt . . . There’s no question that rewiring goes on all the time.” Is this type of shift in brain wiring any different than, say for instance, when written language was introduced to civilization for the first time? Surely, brains were rewired as oral culture was introduced to the written word.

As we consume all of this information, what is the affect on the transference of knowledge? Without having performed any studies, I can only guess that all learners aren't necessarily applying or transferring the information they acquire into knowledge that can be represented and produced. It's one thing to perform a Google search, but it's an entirely different notion to synthesize the information acquired through Google searches into something critical that can ultimately produce knowledge.

I'm reminded of what professor John Black said in my Cognition and Computers class this semester:

The imagination is necessary for transference.

Makes sense.

So, as more media we consume and the more digitally connective we become, what happens to our imaginations, to our thinking processes of reflection and contemplation? Can our imaginations survive in the digital age?

Trying to Move Forward (MSTU 4020; Week 8)

This is exactly what I look like while typing this post & trying to narrow down a topic for the final project (except for the blond hair).

This week's prompt ask 1) What do I think I need in order to move forward on a final project? and 2) how can I get what I need?

The assumption is that I've identified some themes and I've begun to refine my questions. I've certainly identified some themes, though it seems that while trying to refine my questions only more of them spring up. For instance, after reading Nicholas W. Jankowski's article "Creating Community with Media: History, Theories, and Scientific Investigation, I began to ask myself more questions related to Baym's (1999) questions:

- What forces shape online identities?

- How do online communities evolve overtime?

- How does online participation connect to offline life?

- How do online communities influence offline communities?

I've asked similar questions throughout the semester (though stated a bit differently). Here's what I have so far:

- What is the difference between 'real' and virtual?

- How does our participation with/in both 'real' and virtual relate to identity formulation?

- What makes up a virtual terrain; cyberspace?

- What constructs virtual space? Identities? Data?

- What is the relationship between identity and data within cyberspace?

- Does defining the space of cyberspace even matter?

- How does identity formulation occur and knowledge production emerge from/within digitally connective spaces and processes?

- How can we measure identity formulation in relation to our participation with/in digitally connective spaces and processes?

- How can we measure how knowledge production/creation emerges within digitally connective spaces?

- What can other disciplines and theories, aside from sociology and communication, tell us about what cyberspace is, our relation to it, and our participation with/in it (identity formulation & knowledge production)?

So in other words, I have no idea where to begin for the final project.

Moving forward, I really need to hone in on one or two of the questions above. It seems that most of the questions deal with identity formulation and knowledge production, and how we can measure them both epistemologically and ethnographically. The philosophical questions of what is cyberspace? and what constitutes real/virtual? may be, as professor Kinzer noted in class, career-long inquiries (paraphrasing).

In terms of what I need? To be on the look out for more perspectives and readings that address identity formulation, ethnography, discoursive practices, and epistemology of online and digitally connective spaces/processes.

Understanding the Cyberspace Continuum: A Critique (MSTU 4020; Week 7)

The following is a critique on Adrian Mihilache's “The Cyber Space-Time Continuum: Meaning and Metaphor” for a graduate course Social & Communicative Aspects of the Internet at Teachers College, Columbia University. Abstract Adrian Mihalache’s article “The Cyber Space-Time Continuum: Meaning and Metaphor” argues against “ready-made” (2002, p. 293) ideas about spatial meanings and metaphors of cyberspace. Mihalache believes that these notions suffer from two major deficiencies: 1) Cyberspace as a preexisting territory and, 2) Cyberspace as a metric space. He points to the works and ideas of poet William Blake as “extremely” useful examples for making sense of cyberspace (p. 29). In the interest of researching connections between theories about space, place, time and practices according to identity formulation and knowledge production through online interaction, I found the author’s arguments persuasive. However, I also found his arguments critique-worthy, particularly pointing to the hierarchal division the author implies between the arts and sciences to understanding the cyberspace-time continuum. Considering Mihalache’s positions, I seek to further investigate the question: How does identity formulation happen and knowledge production emerge from/within digitally connective spaces like cyberspace? This question requires in-depth analyses that borrow from various theories and practices that span across multiple disciplines. Keywords: cyberspace, space-time, place, identity, virtual, real, epistemology, ethnography

Critique

Multiple Meanings, Multiple Approaches: Understanding the Cyberspace Continuum In his article “The Cyber Space-Time Continuum: Meaning and Metaphor,” Adrian Mihalache argues against “ready-made” (2002, p. 293), and mostly scientific, ideas about spatial meanings and metaphors of cyberspace. Mihalache believes that these ideas about cyberspace suffer from two major assumptions: 1) Cyberspace is a preexisting territory and, 2) Cyberspace is a metric space. Mihalache further argues that mathematical operations are not meaningful to interpret cyberspace because they are limited to understanding virtual space as “a set of objects and rules of interaction,” which fail to explain the connection to the real world (p. 295). To interpret cyberspace as a preexisting territory “waiting to be filled” (p. 293), and to describe it using mathematical operations reinforce a false divide between ‘real’ and virtual worlds. Finally, instead of understanding cyberspace as topographical or in relativistic time-space terms, cyberspace, according to Mihalache, is better understood through the works and ideas of multimedia artist, William Blake.

To better understand meaningful metaphorical constructs of cyberspace, Mihalache points to the multimedia technology of William Blake’s plates. Blake’s plates “blended the text and the image” (p. 296) to produce new meaning. Mihalache believes that multimedia technology, past and present, is imbued with aesthetic power and imagination necessary for meaningful production. He relates modern web experience to the function of Blake’s multimedia works in how both mediums “transform . . . events into lived, meaningful experiences” (p. 297). Through analyzing Blake’s multimedia work, Mihalache asserts a view of cyberspace as a place where spatial divisions are useless metaphors based on an the precept of connection.

While I agree that a false dichotomy exists between the ‘real’ and virtual, I find Mihalache’s explanations of interpreting cyberspace ironically narrow. William Blake’s multimedia art and his notions about the Web are powerful examples of interpreting cyberspace. However, in celebrating these metaphorical interpretations of William Blake, namely by rendering scientific notions useless, Mihalache perpetuates (perhaps unintentionally) the very thing he critiques: a false divide. Though Mihalache points to scientific and mathematical concepts to understanding cyberspace, he does so only to set up a hierarchal model that separates the aesthetic from the material. These ideas do not necessarily function independent of one another. Mihalache refers to Blake’s idea that the arts and sciences can exist, but only in “minutely organized particulars” (p. 296). Even Blake’s slight acknowledgment of the interconnectedness between the arts and sciences is further weakened by Mihalache’s commitment to argue against, for example, post-Newtonian ideas, which I believe can provide equally useful interpretations about what cyberspace is and how we can make meaning in, and of, the digital age. To this end, Mihalache seems to forget the peculiar idea that scientific concepts can be aesthetically meaningful. To better understand identity formulation and how knowledge production emerges from/within digitally connective processes, I argue for broader perspectives and insights that span across disciplines. Going forward, I will look toward various theories, disciplines, and practices to address the following research questions:

1) How does identity formulation happen and knowledge production emerge from/within digitally connective spaces?

2) How can we measure when identity formulation happens and knowledge production emerges in digitally connective spaces, particularly in the context of learning environments?

In-depth analyses that employ multiple disciplines and theories may inspire multi-method approaches to pedagogical and ethnographic practices (Leander & McKim, 2003). Notions that perhaps even Mihalache, in the spirit of William Blake’s works and ideas, can appreciate.

References

Leander, K. M. & McKim, K. K. (2003). Tracing the Everyday 'Sitings' of Adolescents on the Internet: a strategic adaptation of ethnography across online and offline spaces. Education, Communication & Information, 3(2), 211-240. doi:10.1080/14636310303140 Mihalache, A. (2002). The Cyber Space-Time Continuum: Meaning and Metaphor. The Information Society: An International Journal, 18(4), 293-301. doi:10.1080/01972240290075138

So Many Questions: Technology, Identity, Space, and Time (MSTU 4020; Week 6)

Not to come across cheesy or hyperbolic, but I must say that I have been enthralled by the topics we've been discussing so far in class. I think it's mostly because I've always wondered about these topics ever since undergrad when I wrote my first paper on the linguistics practices in online chat rooms (circa 2000). Being surrounded with folks who not only share my interests in these topics but offer new ways of understanding and questioning what technology is and what our relationship is to technology has been an intellectual mind blow for me. Because of my experience in class so far, I think I'm well on my way to better articulating ideas that float abstractly in my brain. I've been exposed to other kinds of languaging and theorizing that I believe will help me make better sense of the abstract thoughts about technologies' relationship to identity, space, and time.

Looking back at previous blog posts and notes, I notice the following questions emerge:

- How do the way we use digital technology define us as a society and as individuals?

- Who or what owns the virtual space where we convene socially and intellectually?

- How are we producing knowledge via the Internet and digital connectivity?

- Who are we in 'real' space? Who are we in virtual space?

- How do our digital worlds see us?

- Why do we think there is a separation between who we are offline/digitally disconnected and who we are online/digitally connected?

I recently published an article on The Loop 21, "Who Are You in the Digital Age?" which asks similar questions about technology and identity.

The following themes continue to pop up in my head:

- Space

- Time

- Geography, topography of non-physical space

- Identity/place

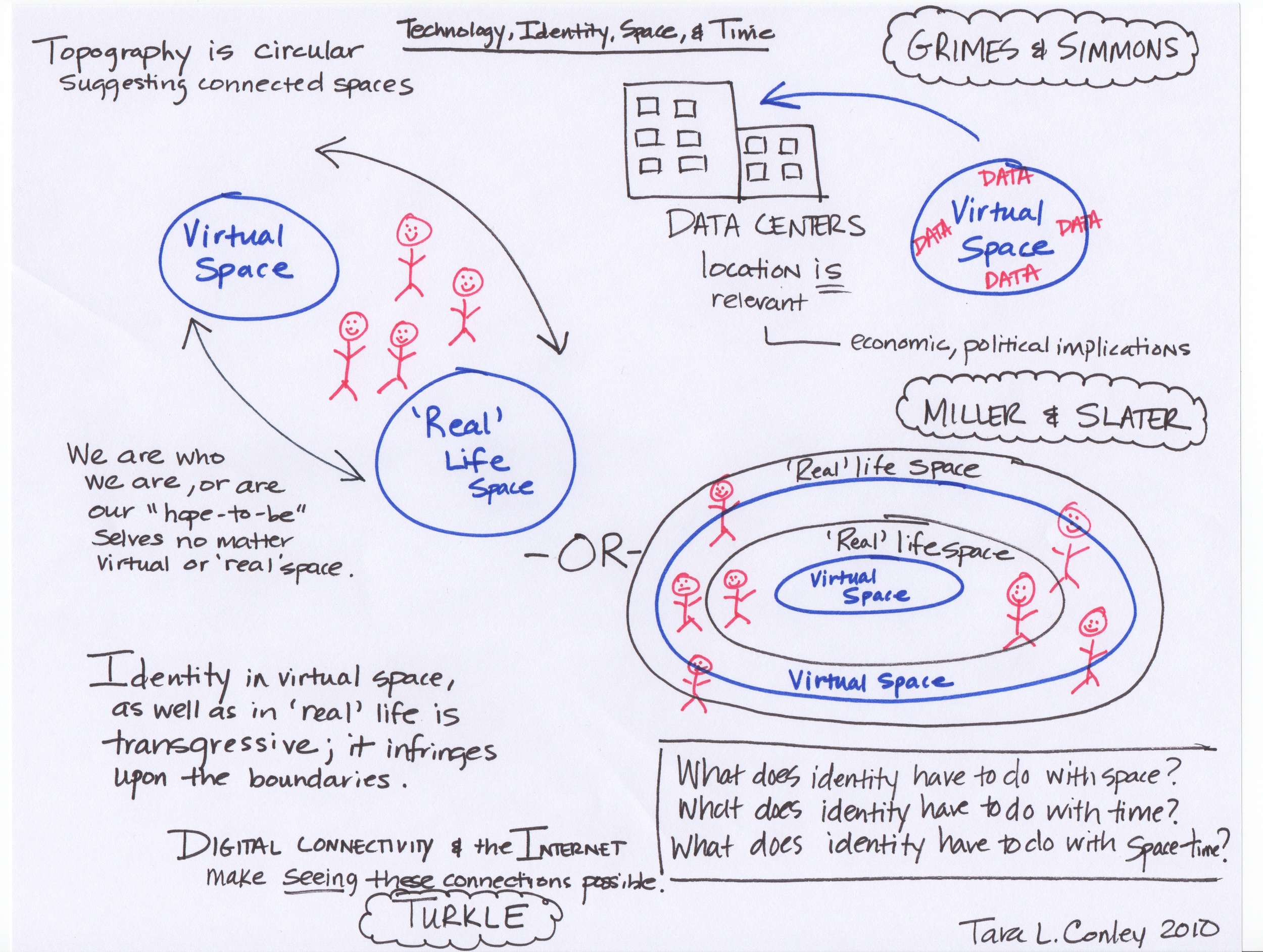

I'm still mulling over the connections between digital connectivity, space, time, identity, even space-time, if there is such a connection. My brain was working overtime when I created the following flow chart/image collage (see below). I had to draw out my notes and questions to see where the connections might be.

Click to enlarge

In this diagram you'll notice some of the questions illustrated above, along with new questions such as:

- What is 'real'? What is virtual? Are these ideas separate or connected?

- What constitutes the boundaries between 'real' and virtual?

- Is virtual space constructed by data? Do we build it? Or do our identities build virtual space (I'm thinking of Miller and Slater's article specifically)?

I don't believe that we are dis-embeded or disembodied according to the geographical or spatial location. Though I learned from this week's readings that data (unlike the concept of identities in virtual space) can be located, collected, managed, and stored. It's not simply a random entity that's "out there somewhere" (see Grimes & Simmons article). BUT, looking at the chart I created above, there may be a spatial connection between our identities and data...Hmm.

With all of that said, one thing seems certain; that digital connectivity and the Internet makes seeing these connections possible (see Turkle article).

My thoughts and ideas about these topics are still very much a work in progress. I'm interested in hearing your thoughts about the connections between technology, identity, space, and time.

FYI - I'm currently reading Janna Levin's book How the Universe Got Its Spots: Diary of a Finite Time in a Finite Space. Dr. Levin is an astrophysicist and professor at Columbia University. So if you're wondering why my thoughts seem a bit spacey, that's why.

References:

Turkle, S. (1995). Life on the screen. New York: Touchstone. (Introduction: Identity in the Age of the Internet and Ch. 7: Aspects of the self. -

Miller, D., & Slater, D. (2000). Being Trini and representing Trinidad. In D. Miller & D. Slater (Eds.), The Internet: An ethnographic approach (85-115). Oxford: Berg. -

Jaeger, P. T., Grimes, J. M., & Simmons, S. N (2009, May). Where is the cloud? Geography, economics, environment, and jurisdiction in cloud computing. First Monday, 14,(5 – 4). URL: http://www.uic.edu/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/rt/printerFriendly/2456/2171

Identity, Representation, and Death in Virtual Space (MSTU 4020; Week 5)

The following post is a weekly response for a graduate course on Social & Communicative Aspects of the Internet at Columbia University, Teachers College. I invite all Media Speaks readers to engage by adding comments below.

I enjoyed engaging with this week's readings because issues of identity and representation in virtual space suit my research interests at this point. I was particularly drawn to Sherry Turkle's chapters "Introduction: Identity in the Age of the Internet" and "Aspects of the Self." Though published in 1995, Turkle's ideas about self representation through virtual spaces are still relevant today. I wasn't too familiar with MUDs (Multi-User Domains) before reading Turkle, though I immediately associated MUDs with Twitter and Facebook, particularly concerning how people use these spaces to interact and create community. Below are a few ideas from each chapter that are worth noting as we think about identity and representation.

From "Identity in the Age of the Internet"

- "The culture of simulation affects our ideas about mind, body, self, and machine" (10).

- The self is constructed (10).

- "On MUDs, [and I'd also argue on popular social networks of today], one's body is represented by one's own textual description" (12).

- Computers have identities (18).

- "Are we living life on screen or living in the screen?" (21).

From "Aspects of the Self"

- As we enter virtual communities we reconstruct our identities (177).

- The Internet is another means of explaining or perceiving identity as multiplicity (178).

- "More people experience identity as a set of roles that can be mixed and matched, whose diverse demands need to be negotiated" (180).

- "Do our real life selves learn lessons from our virtual personae?" (180).

Turkle also discusses mental health in the context of virtual life; do MUDs, or social networks, exacerbate difficulties or contribute to personal growth? I'd argue that we cannot necessarily approach this issue as an "either/or" problem. Virtual life and social networking can magnify mental and emotional afflictions but perhaps participating in these worlds can also provide a way to work through issues since, for the most part, we are still connected to a community of people, some of whom may function as a support system.

I'm not sure I can point to one particular idea that I adamantly disagree with, though perhaps I can expound upon one particular idea Turkle mentioned in the Introduction.

She writes that "one's body is represented by one's own textual description" (12). I wasn't sure if Turkle was referring to textual description as only written text or including other modes. The body surely can be represented (or manipulated as Turkle's seems to be implying when referring to textual description) through other modes like visual description, as in still and moving images.

Take for instance post-mordem photography presented in virtual space. How is the self represented through death? How is the body represented through the dead's visual description?

I thought about an art exhibit that a photographer told me about while we were discussing (on Twitter) the implications of taking still pictures of the dead. The discussion revolved around representation, privilege, and what death or dead bodies mean as we view them in photography. Needless to say I was struck by the images below (see link). I also thought about the cultural/social meanings associated with the idea that a white photographer (Elizabeth Heyert: http://www.elizabethheyert.com/) snapped photos of dead black bodies. I believe the family of the dead allowed the photographer to take these pictures. Still, there's something unsettling about the presentation of images, especially as these images are digitized and widely accessible via the Internet. I can't help but wonder about the photographers relationship to the images and her "use" of them through exhibition, and too, our perception as the virtual viewer of the body as it represents death.

http://www.mediamatic.net/page/65222/en (Warning: These images may be unsettling).

I think issues of identity and representation of human life, and even death, are truly fascinating because the Internet itself is, as Turkle argues, a means through which we can see identity--as well as community and language--as multiplicity.