NOLA Native Shares Scenes from Hurricane Isaac

Our friend Marcus Akinlana has graciously allowed MEDIA MAKE CHANGE to share his photos from the aftermath of hurricane Isaac. I spoke with Marcus yesterday and he told me that he and his family decided to stay in NOLA, bunker down and wait out the storm. Their homes sustained minor damage, but surrounding areas weren't as fortunate. Marcus told me that Plaquemines Parish got hit harder this time around than in 2005 when hurricane Katrina ravished the city. It's hard not to remember Katrina's devastation while looking at the scenes and images below.

I asked Marcus if there is anything we can do to help support recovery efforts. Marcus told me,

"You are a sweetheart! I don't know what to tell you but when it all calms down make a trip to NOLA and come party with us. That's what we like. Come join us on Sunday evening in Congo Square. That'll help. When you can afford it and make the time, come."

As I plan for another trip to NOLA, I'll continue to keep my neighbors the the south in my thoughts and mediations. You can also help by contacting the Red Cross at 1-800-RED CROSS or texting "REDCROSS" to 90999 to make a $10 donation. You can also follow @NOLANews on Twitter for further updates.

Please share your resources, information, and stories below in the comments section and on Twitter using the #RememberKatrina hashtag, and by following @mediamakechange.

Related stories

BP to donate $1 million for Isaac recovery efforts (LSU Reveille)

Verizon Wireless supports hurricane Isaac relief (Sacramento Bee)

#RememberKatrina: A National Conversation Through Digital Storytelling

In 2005 I didn't know what digital storytelling meant. The term had never crossed my mind. I just remember feeling compelled to tell a story with my old Panasonic Camcorder PV-L779D. I was a citizen journalist with a Myspace blog who aspired to be a documentary filmmaker.

Six months fresh out of college and less than a year into my first real teaching job in Houston, Texas, I found myself tracking cable news and Internet stories about the aftermath of hurricane Katrina. Twitter and Facebook weren't in my life at the time so Bill O'Reilly, Anderson Cooper, and Yahoo! News were the next best things. In one day, I had listened to over fifty televised broadcasts coming out of NOLA that highlighted missing children, dying grandmothers, and dead animals. I became obsessed with these stories to the point at which I too became depressed. I found refuge in blogging on Myspace about my experiences meeting survivors, which would later be archived in the Hurricane Digital Memory Bank. But as a twenty-four-year-old middle-school English teacher, I struggled to talk with my students about a natural disaster that happened 350-miles away. I couldn't articulate the calamity of a national tragedy using only words.

When I heard that survivors from NOLA were being bussed to the Houston Reliant Center--my backyard at the time, I dusted off my Panasonic camcorder and headed down 288-South. I didn't know what story I wanted to tell, I just knew that I wanted to talk with survivors and document their stories without the punditry, political diatribes, corporate influence, and commercial breaks. I also wanted to tell my story as a volunteer with the Red Cross.

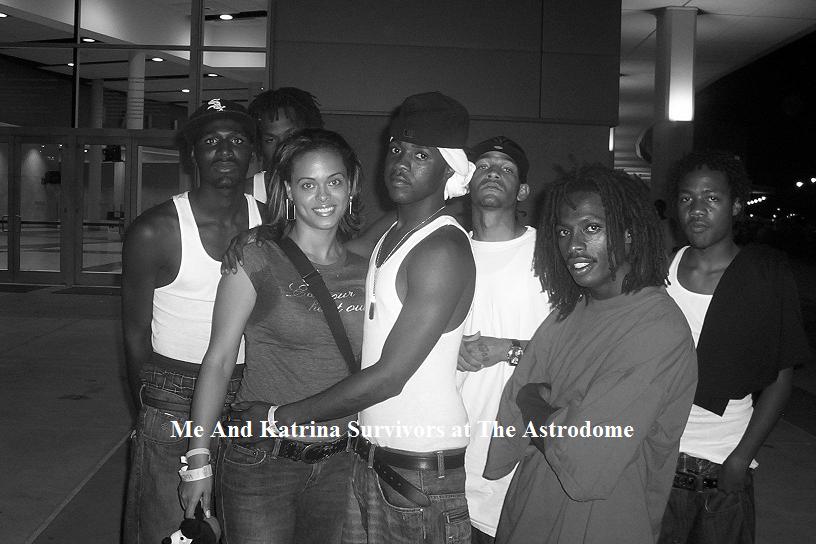

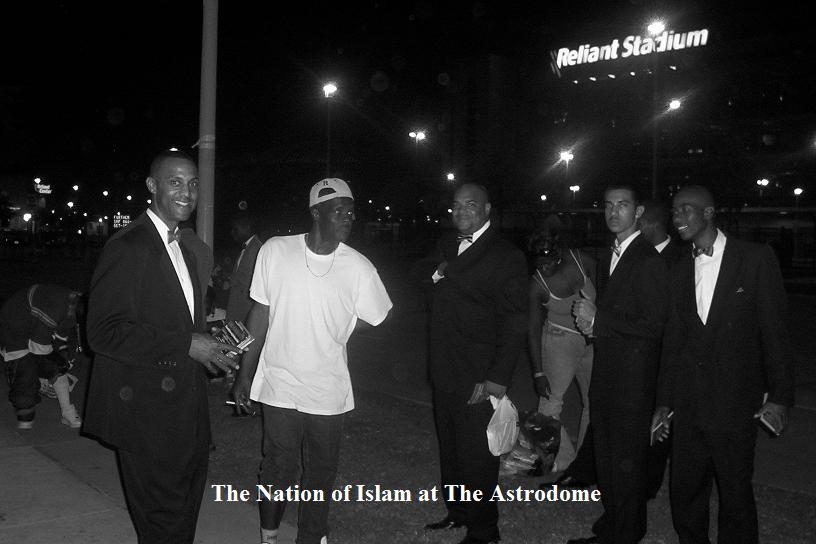

During those few weeks of volunteering, I had the opportunity to get to know survivors through storytelling. I listened to them talk about how lucky they were to be rescued from the top floors of their homes and rooftops. They told me about losing all confidence in their local and state governments. Some stories I heard while standing in-between cots. Other stories I captured on camera while standing outside of what was then called "Reliant City".

After hours of volunteering and recording, I returned home mentally drained and emotionally depleted. I crawled into bed and turned the camera on myself. "This shit's getting to me," I said whipping away tears. "I can't go to sleep because I keep thinking about these people. I just want to help them." I was overwhelmed by the reality that the lives of 70,000+ U.S.-Americans would be consequentially altered forever. I knew that our country would never be the same. She'd be forced to confront a sordid past of racial inequality and political ineptitude, long before President Obama would become president 3 years later.

Looking back at the moment I broke down on camera, I realize now that I sounded like a naive and idealistic child. I thought that maybe documenting my tears and curses on camera could make a difference. I didn't realize I was up against a nation of forgetters.

The Statistics

Since hurricane Katrina there remains approximately 35,700 blighted homes and empty lots in New Orleans alone. The NOPD recently reported a 10% increase in overall crime in the city. Residents in neighboring states like Mississippi who were also affected by Katrina have seen noticeable spikes in insurance payments. For many neighborhoods affected by Katrina all that remain are cement blocks and overgrown weeds where homes once stood. Among the most devastated neighborhoods in NOLA is the Lower Ninth Ward, comprised of 95% African Americans. Despite $14.5 billion in floodgate and levee reconstruction, neighborhoods like Lower Ninth Ward remain noticeably neglected. Though NOLA has seen a diverse population increase since hurricane Katrina, its economic, social, and environmental trends remain troubling. Job cuts in major industries like tourism, oil and gas, and shipping, coupled with unaffordable housing costs, high crime rates, and loss of wetlands contribute to the mounting problems the Big Easy currently confronts since hurricane Katrina.

In efforts to remember our history, MEDIA MAKE CHANGE has launched #RememberKatrina, a national conversation through digital storytelling and social media. All this week, beginning Monday, August 27th through Friday, August 31st, MEDIA MAKE CHANGE (@mediamakechange) will engage in a national conversation with people around the country affected by hurricane Katrina. We begin our conversation on Twitter with several invited guests who will talk about their experiences and research related to hurricane Katrina. The goal is to get as many people talking on social networks, blogs, and via digital video. We believe that the power of storytelling can influence social and political transformation.

#RememberKatrina Is Personal

When I look back at the beginning of my journey as a media maker and educator, I see hurricane Katrina. I recognized that the events leading up to, during, and after the storm inform my current practices as an educator and media maker. These events made me a stronger listener, and in turn, a better storyteller. I learned how to pay attention to what wasn't being said so I could seek out what actually should be told. I developed a sharper eye so I could see through the propaganda and towards counter-narratives for truth-telling.

Since 2006, I've used my amateur documentary about hurricane Katrina, A Region of Survivors to connect with various communities. I've presented my work at universities, community centers, and conferences across the country. As a result, I've engaged professors, students, and community organizers to think critically about social, economic, and political issues relating to the most devastating (un)natural disaster in modern U.S.-history. I parlayed digital documentary, and subsequent other media, to build a community of rememberers. All this because of a storm and some broken levees.

Tell us your stories and join the conversation on Twitter all this week using the #RememberKatrina hashtag.

Lucky: A Katrina Survivor

The following entry is from a 2005 Myspace blog post that I wrote on the first night I returned home from volunteering with the Red Cross in Houston, Texas. The events took place some time around two weeks after hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast. Please do not re-print or re-distribute without express written consent.

Lucky and me (2005)

Current mood: nostalgic

Category: Blogging

A true story.

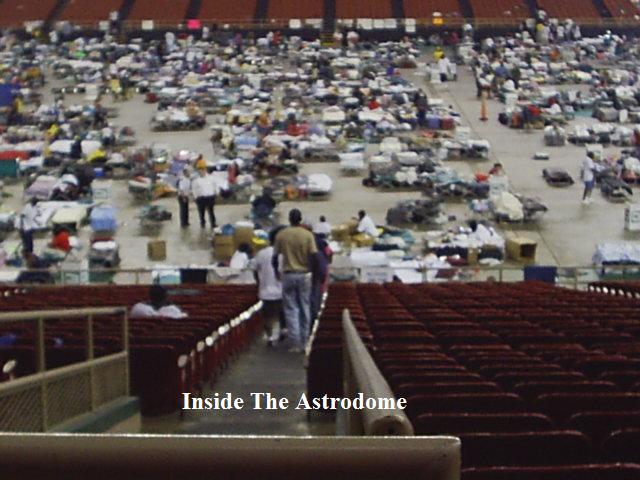

Every night I stepped foot inside the Astrodome in Houston, Texas I was draped with grief from thousands of New Orleans survivors. Each night I walked away from the Dome I was determined to cleanse the muddy perception I had of my own life.

I walked self-consciously between the cramp isles of Red Cross cots spread across the Dome floor. An elderly man in a wheel chair followed closely behind. When I saw him I thought he would be a perfect person to approach since it was our job as volunteers to initiate conversation with residents staying at the Astrodome. Some survivors were in need of blankets and toiletries, others just needed someone to talk to. I've never been comfortable initiating conversations with complete strangers, especially knowing that they've been through so much hell. I couldn't possibly empathize with what the survivors have just gone through. I was nervous and felt out a place. Half of me didn't want to be there.

The old man slowly wheeled his way towards me. I still couldn't speak. Then my father, who came along to volunteer with me, turned toward the old man.

"Hey buddy, how ya doin?" He asked.

Daddy could talk to anyone. I secretly envy him for that.

I was glad Daddy came along, not just as buffer, but because it's been a long time since we had a chance to do something together as equals. I've spent so much of my adult years trying to be the mother to my father instead of just being his daughter.

I stood there looking at the old man, feeling invisible, wanting to say the right thing, but couldn't. Daddy spoke again.

"How did you get here?" Daddy asked.

"Luck," the old man responded.

Daddy asked the old man his age. When he said that he was born in 1930, an immediate pact was formed between the two of them.

"You were born in 1930?" Daddy asked as if he didn't hear him right the first time.

The old man nodded.

"So was I."

Daddy shook the old man's hand, and within an instant that unspoken gesture launched a spontaneous camaraderie between the two and forced me even further away from their pact. Their connection made me inadequate. I wanted to bond too. That was my job as a volunteer.

The old man told us about how he escaped from his home in New Orleans just in time before the water began to swallow his house. He was sleeping when the hurricane hit landfall. People from outside were screaming for him to get out of the house. Something, he told us, woke him up . The next thing he remembered he was being rescued by boat floating down the street.

"I'm just grateful my wife died years before all this. She wouldn't have made if she was there with me when Katrina hit. She was sickly." He told us.

He talked about his late wife as if she was still alive.

"We got married when we was young. It's our 50th anniversary this year." He told us. I looked at Daddy. His eyes were glazed over.

The old man told us that the he was rescued by a U.S. Coast Guard, who then took him to the Convention Center in New Orleans. He spoke about the horrific conditions inside the Convention Center. No electricity, feces and garbage mounting as the hours passed. He talked about hearing rumors that little girls were being raped at night. He felt abandoned.

"Horrible, just horrible!" He shouted while shaking his head.

He said that people feared they would die and blend in with the already dead. Optimism quickly turned into fatigue. Hopelessness took over and darkness filled the arena, forcing imaginations to scamper untamed.

I stood frozen in the telling of his story. My eyes locked in to his words. Though I couldn't hear what he was saying, I could see every syllable of every word drip from his mouth. It was the rhythm of his words that held me in slow motion. The more he reflected upon a history only two weeks old, the lower his eyes fell toward his lap. He was visibly tired.

"I don't have nothing no more. All my things is gone."

"What all did you lose?" I finally asked, breaking my stream of conscious thoughts.

He told us that he lost his home and everything in it.

"But even though my stuff is gone, I'm lucky cause I still got my life. I'm so lucky."

After an hour of talking, Daddy and I decided to pack up our things. It was getting late and volunteer hours were almost over. Before I said goodbye, I promised the old man that I would come back to visit. The old man looked at me.

"You coming tomorrow, right?" He asked.

"Of course. I'll be here," I said.

He told me to reach down under his bed. He had a gift for me. It was a rose. Some family members on the other side of the Dome had stopped by his cot earlier with flowers. He told me to take one just in case we don't see each other again.

Daddy and I left the Dome around 9 o'clock. During our ride home we talked the entire time like two old war vets reminiscing after decades of being apart. When I realized that we never got the old man's name, Daddy said, "we'll call him Lucky."

Tell us your story on Twitter using the #RememberKatrina hashtag

Follow us @mediamakechange

#RememberKatrina

On Monday, August 27th MEDIA MAKE CHANGE (@mediamakechange) will launch the #RememberKatrina hashtag via Twitter. #RememberKatrina seeks to engage a national conversation about hurricane Katrina through storytelling and social media. We've invited several guests to lead the conversation all next week to discuss issues about post-Katrina relief efforts, research, and the status of communities in the Gulf Coast seven years after the storm.

Confirmed participants for #RememberKatrina include:

Marcus Akinlana (@MAkinlana) - a NOLA native, artist, and community activist. His critically-acclaimed art and music has been showcased around the country. He's been a committed cultural advocate for NOLA communities before, during, and after the storm.

Patricia Stukes (@jusbcas) - a doctoral candidate and native New Orleanian lesbian attending Texas Woman's University. Patricia is currently conducting research on lgbti identified advocacy organizations in Baton Rouge and New Orleans since Hurricane Katrina. She is interested in stories regarding lgbti identified persons and how they negotiated disaster recovery. Some of the big questions she is asking include; what is the role of lgbti advocacy organizations in the aftermath of a disaster event like Hurricane Katrina? Does sexuality impact the way in which groups begin the recovery process? Does sexual orientation matter when sexual minorities apply for assistance from faith-based organizations? It is important to think about disaster and the potential environments left before they happen so that minority groups are sustained after the event?

Kellen Smith (@provondatrack) - a NOLA native and artist. He's been featured in two digital documentaries on hurricane Katrina, including A Region of Survivors and Story Melodies Vol. 1: A Tale of Two Cities.

Myron Strong (@AllRealDeal) - a PhD candidate in sociology at the University of North Texas and an Adjunct professor of sociology and women studies at Baltimore City Community College and Community College Baltimore County. His areas of interest include gender, race, social relationships, and pop culture. He has publish articles on pop culture phenomena such consumerism and video games, as well as ideology and education. His current research explores gender role ideology of Blacks and Whites between the ages of 18-30.

MEDIA MAKE CHANGE wants as many people engaged in this conversation as possible. Share with us your reactions upon first hearing about hurricane Katrina in late August of 2005. Talk about ways you and others can support individuals and their communities affected by Katrina and disasters that followed, most notably the BP Oil Spill. Use social media, blogs, and digital video to share your stories.

Some Numbers

It's been nearly seven years since hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast, leaving thousands of US-American citizens homeless and displaced. Since then, impoverished communities still struggle to recover. Perhaps more than any other city located in the Gulf, New Orleans continues to struggle to rebuild neighborhoods severely affected by the storm. Among the most devastated neighborhoods in NOLA is the Lower Ninth Ward, comprised of 98% African Americans.

According to the Greater New Orleans Community Data Center, "there are an estimated 35,700 blighted homes and empty lots in New Orleans (down from 43,755 in September 2010)". Last year, I spoke to native resident Kellen Smith, who told me that "New Orleans is actually worse because the jobs are less, which means more crime."

In 2011 alone, NOPD reported a 10% increase in overall crime (however, murders were significantly down during the 1st quarter of the year).

Though the government has spent $14.5 billion in floodgate and levee reconstruction, neighborhoods like Lower Ninth Ward remain noticeably neglected. With hurricane Isaac currently barreling down the Panhandle and towards NOLA, one can only hope that this high priced infrastructure will be worth the cost.

Despite these statistics, many NOLA residents I've spoken to remain optimistic. Though there is a sense of indifference to tourism's impact on the economy, NOLA's rich culture remains strong primarily because of resilient residents and their stories.

We believe that storytelling can inspire social change and impact policy. So in efforts to continue the national dialogue of remembering our neighbors and rebuilding communities post-Katrina, MMC invites you to join us and follow the conversation on Twitter all this week at @mediamakechange #RememberKatrina.

Related stories

On Katrina's Anniversary: A Bit of Homework (Melissa Harris-Perry Blog)

Vast Defenses Now Shielding New Orleans (New York Times)

From Virtual Volunteers of Katrina to Cyberactivists of Arab Spring

Story Melodies Vol. 2: A Tale of Two Cities

Teaching The Levees (Teachers College, Columbia University)

Image Source

Event Raises New Questions About Code as Literacy, Code as Culture

On Friday I attended Kitchen Table Coders Presents: Learn to Code from an Artist at the New Museum of Contemporary Art. The panel discussion was the first of a two-part series/workshop that featured artists and educators in the fields of programming and design. Panelists included, Amit Pitaru (co-founder of Kitchen Table Coders), Sonali Sridhar (co-founder of Hacker School), Vanessa Hurst (co-founder of Girl Develop It), Jer Thorp (artist and lecturer), and award-winning author and documentarian Douglas Rushkoff.

On Friday I attended Kitchen Table Coders Presents: Learn to Code from an Artist at the New Museum of Contemporary Art. The panel discussion was the first of a two-part series/workshop that featured artists and educators in the fields of programming and design. Panelists included, Amit Pitaru (co-founder of Kitchen Table Coders), Sonali Sridhar (co-founder of Hacker School), Vanessa Hurst (co-founder of Girl Develop It), Jer Thorp (artist and lecturer), and award-winning author and documentarian Douglas Rushkoff.

The panel was unlike most talks I've attended about computer science and technology namely because the panelists were artists and educators speaking about coding and programming as expression. The discussion consisted less of tech jargon, and more so included insights about how coding can be a creative process with which many people, not just computer engineers and master programmers, could engage. Being that all of the panelists were educators, the conversation also focused on how we can best teach code to novice and master programmers. Jer Thorp, in particular, was less concerned about producing the next generation of workers, but more so interested in helping to create a code literate generation.

"What we’re seeing now is that code is being taught to produce workers, not to necessarily produce expressive authors of code and art. It's like we're producing technical writers as opposed to producing novelists."

Douglas Rushkoff began the discussion by asking the panelists several thought-provoking questions about code literacy---the ability to read, write, and think critically using computer programming languages. Among the questions Rushkoff asked included:

- How do we make people aware of this space?

- Is learning how to code what we should be teaching the world?

- What are the biases of digital space?

- What do we need to communicate about code to the public?

- What’s the difference between a user and a programmer?

- Do we have to know how to code in order to participate meaningfully in a digital world?

Concerning the last question, the panelists all agreed that learning code does allow for more meaningful participation in a digital world. Amit Pitaru stated that "we should at least be able to read code, maybe not write it at first." Similarly, Sonali Sridhar noted that learning code "opens up the black box" of knowledge. She spoke about how learning code changed her perspective about everything around her, from the way buildings are structured to how gadgets work. Vanessa Hurst echoed her colleagues' sentiments and added that learning code is not simply about solving problems that have already been solved, but about being able to tackled unsolved and complex problems.

"I'm not comfortable with solving problems that are already solved," said Hurst.

The panelists also discussed how learning code can be both a social and solitary experience. They mentioned that most master coders have put in 10,000+ lonely hours tinkering around, mostly failing, but constructing new and innovative projects as a result. Sridhar's Hacker School operates mainly as a self-learning model, but also functions in a collaborative space of newbie and master programmers. Pitaru noted that Kitchen Table Coders is an open source model available to anyone willing to adopt its structure as means of learning code.

"At Kitchen Table, you wouldn’t know who’s teaching and who’s the student because everyone is sitting around a table learning from each other," said Pitaru.

I was particularly interested in Sridhar and Hurst's experiences as women coders and educators. Sridhar mentioned that for women, "there's an immense amount of fear in this space." Hurst, who works with women at Girl Develop It, agreed that even though women are just as capable as men to program, they're less likely to have a sustained interest in computer science in the long term, with girls tending to disengage in the field once they reach middle school.

Toward the end of the session, I asked the panelists to talk more about code as culture and code as art. Specifically, I asked:

- Where is the culture in code? Is code gendered, raced, classed? If not, do we want it to be?

- Is there emotion in code? If so where is it?

To the second question, Pitaru responded saying that “emotion is not in the code, it’s in coding (the action of code)." I can attest that learning how to code, and the act of doing code, can be both a frustrating and satisfying endeavor. Technologist, Ann Daramola would likely agree.

Hurst told the audience that code shouldn't be gendered, raced, or classed, although the reality is that computer science is largely a white male industry.

Both Sridhar and Hurst cited the book Unlocking the Clubhouse: Women in Computing as a useful primer source on the topic of gender and computer science. Rushkoff chimed in stating that the cultural perceptions we have about computer science is problematic. He mentioned research studies that prove girls are just as good as boys at mathematics, but our cultural perceptions skew this reality.

But even if we all agree that cultural perceptions influence the ways in which traditionally marginalized groups participate in computer science and STEM fields, we also have to acknowledge the structural forces at play that impact the participation gap between white middle class males and girls, people of color, and immigrants.

Gender stereotypes, racial discrimination, socio-economic status, and citizenship all influence the pipeline to higher education and STEM careers. Even time to tinker and play with a computer is a privilege for a large number of gendered, raced, and classed communities.

I would have liked to hear the panelists speak more about how race and class dynamics, not simply gender, impact code literacy, but perhaps that's another panel discussion entirely, and one that I hope will feature more programmers, educators, and researchers of color.

After the panel discussion I had a chance to briefly chat with Hurst about what I'd like to accomplish with my research regarding girls, youth of color, and immigrant coders. She noted that one of the reasons why the Unlocking the Clubhouse is always cited by women in tech is because the field is desperate for new research in computer science at the intersection of gender, race, and class.

Lack of research in this area may present challenges for those curious about the cultural aspects of computing. However, this shortage of knowledge presents a great opportunity for researchers like myself who are intent on exploring the interplay between culture and computing, especially given that gender, race, class, sexuality, and citizenship all matter in this digital moment.

Related resources

Amit Pitaru @pitaru

Sonali Sridhar @jollysonali

Vanessa Hurst @DBNess

Jer Thorp @blprnt

Douglas Rushkoff @rushkoff

Kitchen Table Coders @ktcoders