When Qualitative Study Goes Wrong (MSTU 4020; Week 10)

Maybe the title's a bit hyperbolic and maybe I'm a bit frustrated with some of the readings this week because my brain is fried and it's 1:00 am.

Nonetheless, I found The Benefits of Facebook "Friends" profoundly cumbersome. I will concede to the fact that my view of any scholarship on Facebook at this point is nauseating. I feel like we're all staring at a chimpanzee at the zoo as if to study it from a distance only to realize the chimpanzee is really our own silly reflection in the glass window. We're hell bent on finding something "new" or interesting about something that's not really that new or interesting anymore -- at least that's what it seems like. The initial response to Facebook was certainly warranted. Mark Zuckerberg's a genius. Social networking is sexy. And algorithms are the new black. I get that we're entirely obsessed with wanting to understand more about ourselves and our communities. The Internet is a fantastic means of seeing and studying those ideas. But what are we truly getting out of it all?

I have a hard time wrapping my brain around how qualitative studies like The Benefits of Facebook "Friends" have managed to quantify bridging, bonding, and maintaining relationships to the Cronbach’s alpha statistic. This is utterly mind boggling. As I tried to skim the article for definitions of what the authors mean by bridging, bonding, and maintaining relationships, all I found were references to other authors' scales, followed by some random (okay, not random) equation. *pulls out hair* Do we really need statistical data to represent an understanding of how people feel and interact on Facebook? Granted, maybe we do, but boy-oh-boy western society sure does pride itself on rationale and objectivity through scientific measure, even to the point that something qualitative must be quantified.

The fact that nearly all Facebook users include their high school name in their profile (96%) suggests that maintaining connections to former high school classmates is a strong motivation for using Facebook.

Um, okay. Fascinating stuff. So what about those who don't include their high school names, are they less likely to want to maintain connections to former high school classmates? What if the motivation to not include their high school name has absolutely nothing to do with maintaining connections with former classmates? What if that 4% still wants to (and do!) maintain connections, but inserts "High School of the Gifted Pocket Protector Posse" in their profile? What's truly in a name?

This excerpt is really only a small (and silly on my part) example of how quantitative data seems, to me anyway, pointless in the realm of study that's overwhelmingly qualitative.

We've already discussed how complex identity (and identifying) works within digitally connective social spaces. Some of these findings, for instance, do not speak to those complexities or nuances of identity representation and formulation whatsoever.

This particular reading, along with some of the others, brings me back to an issue that I've been thinking about throughout this semester. That is, how do we go about researching digitally connective social spaces? What do we, as researchers and educators, need to consider as it concerns emerging ethnographies in the field? I'm nearly convinced that some of the ways in which we've been going about these "studies" are wrong. And I'm not sure what the alternative is at this point. But it does seem as though we're applying odd and useless methods to a complex area of study.

What of these so-called "findings" is necessary (found on p. 1147)?

- Hypothesis 3a (supported): The relationship between intensity of Facebook use and bridging social capital will vary depending on the degree of a person’s self esteem.

- Hypothesis 3b (supported): The relationship between intensity of Facebook use and bridging social capital will vary depending on the degree of a person’s satisfaction with life.

Talk about mixed ideas; self esteem, social capital (what an abstract notion!), bridging. Is this a psychology study or a study I'd find in a business journal? Even the languaging is wretched.

Aside from the study itself, I worry that the lure of researching SNS outweighs it's effectiveness for educators and scholars. It only seems that these sort of studies are useful stats to inform media soundbites or marketing/PR talking points, but what value do they have toward our understanding of phenomena in communication, societal shifts, technological usefulness, and education (beyond what we already know about physicality, virtuality, embodiness, etc.)? Maybe I'm bothered that the studies aren't moving as fast as the technology itself. Or maybe it's that the studies aren't broad enough in scope (what about Twitter?). Or maybe it's the lateness of the hour and the moment of intellectual exhaustion. Whatever the case maybe, I recognize something unsettling in my gut about all of this sort of research. I really want us to go somewhere with it, to see something truly remarkable about who we are as people and as communities. I want this area of study to inform what else is out there beyond our localities and our realm of awareness. But I just can't see anything biting beyond the proverbial glass window.

On another note, thank God for SuperNews.

Are Net Geners Really Tech Savvy Learners? (MSTU 4020; Week 4)

The following post is a weekly response for a graduate course on Social & Communicative Aspects of the Internet at Columbia University, Teachers College. I invite all Media Speaks readers to engage by adding comments below.

I was delighted to read Kirschner and Karpinski's article "Facebook and Academic Performance" because I'm sure this article will continue to spark plenty debates between educators and professionals, as indicated in the First Monday journals. I had first heard about the statistic that "Facebook users have lower GPAs and spend fewer hours per week studying than non-users" via Twitter. Kirschner and Karpinski's findings were significant enough to be published on TIME, although the media hype surrounding the article is a major academic criticism of the study overall. However, it's also important to mention that there is plenty of room for improvement in this study. The researchers indicate limitations and ways to better improve qualitative data at the end of the article.

Another reason I was highly engaged with this article is because it's relevant to other ideas I've been thinking about lately concerning our new generation of tech users and learners. I often wonder if students and minorities are, in fact, learning via online spaces. How do we understand literacy via online spaces in urban communities as African-Americans mobile users are on the rise, for instance? I posed a similar question about the relationship between literacy, new technology, and urban communities on Twitter a few weeks ago. I cited digital scholar, Allison Clark, who stated (paraphrasing) that we can't research or print a paper using a mobile device. I also wrote an article addressing a similar topic on The Loop 21.

Needless to say, the initial responses I received from Twitter and from my article were from people who immediate came to the defense of mobile technology. Some stated that because mobile technology is so innovative and rapidly expanding that we can, in fact, learn and become more literate through this type of media. Though I'm reminded of the conversation we had last week about the difference between information and knowledge.

Are what we're doing (or learning) by way of Google, Wikipedia, and on mobile devices ("passive consumption of information") a true indicator of knowledge production?

Kirschner and Karpinski's article also asks us to consider whether or not Homo Zappiens or Net Geners (those multi-tasking "techies" born in the 1980s and 1990's) have a deep knowledge of technology, especially when learning-by-doing "is often limited to basic office suite skills, e-mail- ing, text messaging, FB, and surfing the Internet" (1238).

So I wonder, are net geners really tech savvy learners or simply consumers of "low level", passive, or superficial technology? How might we measure knowledge production when the majority of minority net geners are using mobile devices to access the Internet?

And now, your moment of Zin.

Leaping the Gap: Addressing Independence in Underprivileged Communities

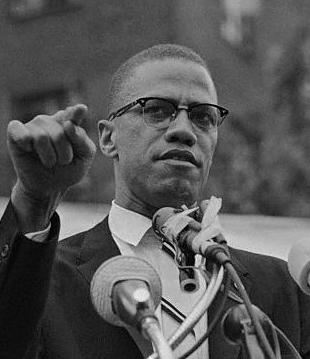

It's amazing to me that in this day and age, very few of us have addressed the issue of independent ownership on the web. With the advent of Media Make Change, and its like-minded allies, we have a venue by which to address the inequities that persist in an increasingly global and digital world. Some of the first things I thought of when it came to addressing "ownership" came from Malcolm X, community organizer. While he's most popular for his radical stances and politics, he's also well-known for his advocacy for community ownership. His idea of ownership stems from understanding that the minute a community invests in their own financial capital, the more they'll invest in their own human capital.

It's amazing to me that in this day and age, very few of us have addressed the issue of independent ownership on the web. With the advent of Media Make Change, and its like-minded allies, we have a venue by which to address the inequities that persist in an increasingly global and digital world. Some of the first things I thought of when it came to addressing "ownership" came from Malcolm X, community organizer. While he's most popular for his radical stances and politics, he's also well-known for his advocacy for community ownership. His idea of ownership stems from understanding that the minute a community invests in their own financial capital, the more they'll invest in their own human capital.

The same applies to the web.

While the percentage of homes with Internet access grows yearly, there's around a 20% difference between percentage of Blacks and Latinos home access and Whites and Asians, so the digital divide persists. Even amongst those of us who have Internet access, regardless of background, we still rely heavily on free services such as Blogspot and Livejournal to host our thoughts, Facebook and Ning to house our networks, and Twitter and (sadly) MySpace for promotions. While many of the reasons why we stick to the free services are purely economical, a few of us with the capita don't invest simply because we would rather outsource our personal information.

And that's where the future lies.

In my case, I relied heavily on free services to host everything I did. I was an early adapter to Facebook, Xanga, Twitter, MySpace, and every other larger scale social network service there was. Then, as my interests expanded, I began to see the limitations of these spaces. I started to see friends in similar fields get their memberships revoked or their material dissolved. Social networks began to change their terms of service to de-privatize personal usage, and some services even began to arbitrarily block certain sites that others deemed offensive, even when others of its like never got any warnings.

Thus, with the help of a few friends, I got my own .com.

Admittedly, this is not a new idea for many of us web savants. Multiplatinum musicians and businessmen advertised this idea in the early 90s. Yet, how to attain this status has escaped those who didn't have access early on. Even I had my fears about jumping into this web on my own.

Still, the cost of freedom is worth every penny. In my journey, these three points helped develop my own presence on this vast Internet:

- I have my own name and extension under which anyone can reach me.

- I have contracted independent hosting (note: the difference here is that the hosting services are beholden to you when you're paying, especially if you know what you're supposed to get)

- I use the free services as a means of networking with those who use the services.

Notice that the relationship here is different. Once you've controlled your own space on the Web, you can now interact on those sites without being beholden to them. In a way, they need you because it's your content that engages your network, particularly when you build a sizable network of your own.

Media Make Change is part of that vision. Building and teaching to a curriculum that serves the people who need this sort of information the most may do well for our prospects in decades to come. Until then, let's work towards our independence, one .com at a time.

How else can we build as a community on the Internet?

Jose Vilson, who wrote a synopsis of this back at his site ...